To write about online gender-based violence (GBV) is to write about everything for it is oppression so pervasive that it is natural and normalised. Yet, it is also to write about nothing. It is rarely new or original even when it is perpetrated online.

Today, more and more women, queers, and allies, in all their diversity are speaking up, exchanging stories, finding language in naming the unspeakable violence, and sometimes, keeping our silence and actively listen to others – we create a bulwark that resists trivialisation and normalisation of GBV everywhere. And this article will not be possible without that. It is the objective of this article to discuss online GBV as a process of political domination and control over women’s agency and voice.

We create a bulwark that resists trivialisation and normalisation of GBV everywhere

As a point of departure, it will be useful to borrow Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung’s triangle of violence, namely direct, structural and cultural violence, in which he offers a unified framework where all violence can be seen. Structural violence is violence without a subject, inherent to the structure of society and political dominance of one social group over others; direct violence is personal, actor-generated and violence with a subject; and cultural violence is where aspect of a culture that can be used to legitimate violence in its direct or structural form.1

Galtung goes further to state that peace can only be obtained on all three corners at the same time, and not assuming that basic change in one will automatically lead to changes in the other two. Direct violence is akin to the tip of the iceberg, visible and known to the minds of people. It is easy to identify, therefore to combat. In actuality the vast formation (structural and cultural violence) is hidden below the water’s surface. Therefore, a holistic approach would focus on transforming the personal, the structural and the cultural, and goes beyond the conception of singular and evil acts.

Direct violence is akin to the tip of the iceberg, visible and known to the minds of people. It is easy to identify therefore to combat.

It must be noted while Galtung acknowledges patriarchy as one form of structural violence, his exploration of patriarchy (beyond a binary approach) and intersectionality of identities leaves much to be desired, but a discussion and examination of Galtung’s theory and feminist’s theories on violence is well beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say that for now the violence triangle offers a preliminary framework where online GBV can be seen in the larger context of cultural violence and a process of political dominance.

It must be noted that men do face online violence – and their experiences too deserves further investigation, especially in cases where they speak up against other men or sexism. However, research has shown that the violence men and women receive differs greatly in substance and quantity. While men receive abuse on account of the views they hold, the comments women receive seem to quickly target their identity as women.2 In some cases, such as distribution of rape videos online, women do not even have to be internet users to suffer online GBV. And where women are active online, online spaces are intricately linked to offline spaces; making it difficult to differentiate between experiences of events that take place online versus events offline events.3

Research has shown that the violence men and women receive differs greatly in substance and quantity. While men receive abuse on account of the views they hold, the comments women receive seem to quickly target their identity as women.

It is a pattern, not incidental

The problem is neither a legal one, nor an isolated crime committed by aberrant individual, nor is it only experienced by women and vulnerable groups in the western countries. If anything, online GBV tends to be exacerbated alongside discrimination(s) based on multiple identities and oppressions.

Example from Malaysia:

A young male member posted a photo of a young woman without her knowledge or consent in the Facebook group created only for members of indigenous communities. The young woman was described as looking “urban” and the caption attached was the young man offering to set up sexual encounters with the woman. As such the post indicates violent disapproval of Orang Asli women integrating into city life or presenting themselves as having personal agency outside of the community. Many men agreed with the post. While some have defended the young woman in the photo and asked for its removal, the post was not removed. The Orang Asli community is one of the most marginalised group in Malaysia and often rendered powerless in their clashes with the might of the state.

As documented in EMPOWER’s report, Voice, Visibility and A Variety of Viciousness

The pandemic existence of online GBV, and the subsequent response by the state and public members remind us that this form of violence cannot be dismissed as marginal or incidental. It is a pattern or part of a pattern, that is not static, it is a process of societal and political control of women’s power and agency coded into our culture and what is perceived as natural and neutral. GBV is neither simple nor monolithic, but sustained and reproduced across spaces, institutions and discourses. It interacts and interweaves with layers of power and cultural aspects around age, gender expression, race, sexual orientation, religion, ability, location etc. producing different impacts on different bodies.

Gender-based violence interacts and interweaves with layers of power and cultural aspects around age, gender expression, race, sexual orientation, religion, ability, location etc. producing different impacts on different bodies.

Would that mean broadening the agenda for online GBV? Yes! To return to Galtung, he contends that the “triangular-violence should then be contrasted with a triangular syndrome of peace, in which cultural peace engenders structural peace, with symbiotic, equitable relations among diverse partners, and direct peace with acts of cooperation, friendliness and love.”

Silencing as violence

Today, even as policy makers and law enforcers gradually awaken to the harm of online GBV, we still struggle in deciding what amounts to violence and what is legally actionable. These challenges are shared with other forms of GBV especially when direct physical harm is not involved, for instance stalking, sexual harassment.4 While some distinctions as to what is actionable and what is not actionable is required, especially when the criminal justice system is involved, it is pertinent that we look at what is excluded, who is making the decisions and on what basis these decisions are made.

While some distinctions as to what is actionable and what is not actionable is required, especially when the criminal justice system is involved, it is pertinent that we look at what is excluded, who is making the decisions and on what basis these decisions are made.

The process of identifying direct violence is inherently gendered and driven by structural and cultural violence that deems women’s voices and experiences as inferior. For a long time, domestic violence and marital rape were considered a private affair and not open to “interference” by outsiders and the state. In 1910, the U.S.A. Supreme Court denied a woman the right to prosecute her husband for assault because to do so it would taint the legal system with a flood of false accusations.5

Research by Association for Progressive Communications (APC) in 7 countries shows, law enforcement typically trivialises technology-related violence against women and victim-blaming is common among police personnel. This results in a culture of silence, where survivors are inhibited from speaking out for fear of being held complicit for the violence they have experienced. As stated in research by Amnesty International on women’s experience on Twitter – “Many of the women interviewed by Amnesty International described changing their behaviour on the platform due to Twitter’s failure to provide adequate remedy when they experienced violence and abuse. The changes women make to their behaviour on Twitter ranges from self-censoring content they post to avoid violence and abuse, fundamentally changing the way they use the platform, limiting their interactions on Twitter, and sometimes, leaving the platform completely.” The same pattern is observed in a research conducted by EMPOWER in Malaysia, where eight out fifteen women who had experienced sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) online were forced to leave social media platforms, inevitably affecting their ability to exercise their right to freedom of expression.

Example from India:

“I become very upset when I am thinking of a response if they say something negative. I have cut down on my reactions to current affairs. I have had people coming and sending me messages like ‘I hope your snotty nose children end up turning into lousy failures in life’ and ‘We curse your children so that they end up absolute useless failures' over email and comments. The negativity plays on your mind. Unke bolne se kuch nahin hone wala [Not that everything will happen as they say]. But do you want the bad vibes directed to your children? Do you really need such negativity in your life? So I have stopped writing about current affairs…”

As documented in Internet Democracy Project’s report, “ ‘Don't Let it Stand!’ : An Exploratory Study of Women and Verbal Online Abuse in India,” page 8

The violence inflicted was never merely physical – the motivation to inflict violence derived from a power structure that seeks to control and silence women, and that violence is legitimised by a sense of entitlement rooted in the cultural belief system. Rebecca Solnit in her book The Mother of All Questions says, “silence is what allowed predators to rampage through the decades, unchecked. It’s as though the voices of these prominent public men devoured the voices of others into nothingness, a narrative cannibalism. They rendered them voiceless to refuse and afflicted with unbelievable stories.”6

Collage by Flavia Fascendini

For a long time, online GBV was dismissed as merely virtual and henceforth not a form of violence. Feminists around the world had through a decade of hard work put online GBV under the spotlight – like in the Take back the tech project. The non-recognition of such forms of violence was built on the absence of dissent, disbelief and the ability to obliterate these narratives. Until something broke. Today, the harrowing silence was broken when an ocean of stories surfaced of online violence, sexual harassment, assault, workplace discrimination etc.

For a long time, online GBV was dismissed as merely virtual and henceforth not a form of violence. Feminists around the world had through a decade of hard work put online GBV under the spotlight.

Everyone is a perpetrator

A distinction between primary perpetrator and secondary perpetrator was made in the issue paper Due Diligence and Accountability for Online Violence Against Women. The former is the person initiating the violence, namely the author, or the person who first uploads the offending data or images; the latter is the person who purposefully, recklessly or negligently downloads, forwards, or shares the offending data or images. Further, the author, Zarizana notes that as it is now, there is legal challenge in holding primary perpetrator accountable due to lack of training, skills and resources on part of legal enforcers, and so little attention and effort are directed to hold secondary perpetrators accountable. “Data and images that are tweeted and re-tweeted, downloaded and forwarded, liked and shared may involve a great number of individuals and pose an overwhelming challenge to regulators.”7

Data and images that are tweeted and re-tweeted, downloaded and forwarded, liked and shared may involve a great number of individuals and pose an overwhelming challenge to regulators.

Online GBV is not only perpetrated by the unscrupulous villain. Everyone can be a perpetrator of online GBV. Friends and family included. A like. A screenshot. A retweet. A sharing. A comment. Several comments. And so, no one is the perpetrator. The internet has made silencing, coercing, intimidating, intoxicating and rejecting women easier, quicker, more efficient. The law may have a response to an event perpetrated by a criminal, but we do not have a legal response to structural inequality and the gendered power dynamic; or a culture that is predicated on hatred, discrimination and violence against women and queers.

The internet has made silencing, coercing, intimidating, intoxicating and rejecting women easier, quicker, more efficient. The law may have a response to an event perpetrated by a criminal, but we do not have a legal response to structural inequality and the gendered power dynamic.

Example from Argentina:

After breaking up with her boyfriend, a woman found that several naked pictures and a sex tape of her were published without consent on a Facebook group that she shared with co-workers. The photos were also distributed on two porn websites (one based in Argentina and another in the USA). She reported the situation to Facebook, Google and other websites concerned, but did not receive a response. She then made a complaint at the Personal Data Protection Center for Buenos Aires Ombudsman’s Office. Whilst the content was finally removed, it is still possible to access to some images from other websites that has republished the content from other jurisdiction.

As documented in Internet Governance Forum (IGF) 2015: Best Practice Forum (BPF) on Online Abuse and Gender-Based Violence Against Women, page 29

States are often fixated on the physical aspect of direct violence and ignore the structural and cultural. To make those changes would mean questioning foundational assumptions that threaten their own (male) privileges. While regulation and criminalisation of direct violence is crucial, without broadening our queries into the structural and cultural causes of violence, as described by London-based journalist Laurie Penny the internet will be nothing but an inverse Hydra, “put down one and two more pop up in his place to tell you your dead dad would be ashamed of you.”8

Freedom of Expression?

There is an underlying assumption that your right to freedom of expression is as good as mine, and that we all have the same power in exercising that right. The right to speak and the right to be seen with credibility is akin to wealth operating in a free market system, where wealth is always not equally distributed and this inequality is usually along the lines of discrimination around location, race, gender, able-bodiedness etc. The mainstream narrative and language have long been concentrated in the hands of privileged communities with audibility and credibility.

APC’s submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on online violence against women notes that “given that violence against women has been recognised as being a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women, and an obstacle to the achievement of equality, development and peace, it follows that incitement to violence, discrimination and hostility against/towards women and gender-based violence fall within the exception to freedom of expression.”9

Provisions against hate speech in international human rights law usually cover grounds related to racial, ethnic, and religious hatred, as with Article 20 (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. While there is no universal definition for hate speech and it varies greatly from country to country, but generally, legal frameworks often exclude incitement to GBV as hate speech.

Generally, legal frameworks often exclude incitement to GBV as hate speech.

The Internet Governance Forum (IGF) 2015: Best Practice Forum (BPF) on Online Abuse and Gender-Based Violence Against Women notes that measures to address online abuse and GBV, especially when it relates to drawing limits around content and expression, is sometimes seen as limiting the right to freedom of expression.10 Many speak of abuse and violence against women and queers online as a right to freedom of expression. Save for cases where direct physical death and rape threat are involved, the rest is an ocean of uncharted waters.

In Peace by Peaceful Means, Galtung says that language is not neutral and it is one element of cultural violence, which serves to legitimize all other types of violence.11 This correlates with feminist works on the gendering of language in reproduction of violence and in silencing women.

Discourse around GBV often gets abstracted and hijacked, which then serve to legitimise violence as a ‘right’. The terms Feminazi, Gal-Quaeda, Social Justice Warriors, are increasingly used on social media to refer to feminists who denounce everyday sexism, gender stereotyping or GBV. They are used to delegitimise their opinions and expression, to silence and demonise the work of feminists. These words, beyond its historical and literal meaning, have a plain and mechanical power. It is a way of legitimising the onslaught of misogynistic abuse and harassment that follows – “you deserve it,” “you provoked me first,” “you had it coming, don’t cry victim.”

The terms Feminazi, Gal-Quaeda, Social Justice Warriors, are increasingly used on social media to refer to feminists who denounce everyday sexism, gender stereotyping or GBV. They are used to delegitimise their opinions and expression, to silence and demonise the work of feminists.

Every time such words and narratives are employed, it reinforces the unequal playing field and power structure. Freedom of expression is essential – a free person tells their story freely. But regardless , freedom of expression is a highly gendered discourse and debunking its egalitarian myth and its enjoyment by mostly privileged groups is important in unpacking the realities of GBV.

Freedom of expression is a highly gendered discourse and debunking its egalitarian myth and its enjoyment by mostly privileged groups is important in unpacking the realities of GBV.

Rule of Law and Rule of Men

Women have for centuries fought for access to justice for survivors of GBV through the legal system. At a personal level, gaining access to justice for acts of GBV is important to uphold one’s legal rights and in securing remedy; politically, it also promotes change at the systemic level, setting a precedent that such acts are not to be tolerated.

However, many would know that when it comes to cases of GBV, the administration of justice is often deficient. When it comes to online GBV, many of the challenges are similar to offline, but the manner in which violence is perpetrated through technology does pose new challenges to the criminal justice system. APC’s research found that women’s access to justice in cases of online GBV was frequently limited due to inflexible interpretation of existing legislation addressing gender based violence, data privacy and cybercrime.12 Similarly, Amnesty International’s online poll shows that 50% of women in eight countries polled stated that the current laws to deal with online abuse or harassment were inadequate.

The challenges are in part due to the globalised and decentralised nature of the internet which allows instantaneous transmission across jurisdictions, and that questions of liability of internet intermediaries and platform providers are still unsettled. An extended explanation of these can be found in the Due Diligence issue paper, also referred to above.

The challenges are in part due to the globalised and decentralised nature of the internet which allows instantaneous transmission across jurisdictions, and that questions of liability of internet intermediaries and platform providers are still unsettled.

Over and above, the tension between the laws and the internet is yet another telltale sign that the law is co-extensive with the interests of those in power. Feminist legal theories have long acknowledged that the law is not neutral. The liberal illusion of neutrality as a surrogate for justice, presents a special obstacle to women due to the historic equation of neutrality with maleness and this obscures more than enhances the debate.13

Catherine Mackinnon, United State-based feminist and law professor, contends that the law effectively institutionalises male power over women and this power is a web of control and coercion that structures women’s everyday lives – in the home, in the bedroom, on the internet, on the job, in the street, in the Parliament, throughout social life. This cannot be altered merely by admitting women through its door, nor will reform help since it will simply produce male oriented results and reproduce male dominated relations already embedded in the law.14 The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) in a guide to women’s access to justice for GBV notes that it is not only laws that need to be reformed but also policies and practices in the administration of justice.

Legal thinking is organized around bottom line dichotomies: law versus policy, public versus private realms, expert versus lay opinion, civilian governance versus military necessity, consent versus coercion.

“Legal thinking is organized around bottom line dichotomies: law versus policy, public versus private realms, expert versus lay opinion, civilian governance versus military necessity, consent versus coercion.”15 Similarly the attempt to draw boundary between what is ‘online’ and what is ‘offline’ in the context of online GBV is often impossible and unhelpful. And in some cases, the punishment for online violence is lighter than physical violence happened on ground.16 The false dichotomy between online and offline underlines that physical violence is embedded into judicial and legal thinking around any questions of violence. Harm arising from online violence, especially where physical harm is not involved, is hard to observe and verify, and to the judicial mind recognising such form of harm is a slippery slope that apparently prefigures the likelihood of rampant judicial oversensitivity (for e.g. finding School Girl Zombies with Deep Throats pornographic in a current decision prefigures the likelihood of a decision that finds ‘The Little Mermaid’ pornographic). For the process of identifying harm is gendered. The rule of law or the rule of man is an institutionalised form of male power and the male point of view. Rape law assumes that consent to sex is as real for women as it is for men. Privacy law assumes women in private spaces have the same privacy as men do. Obscenity law assumes that women have the same access to free expression as men do. Equality law assumes that women are socially equal to men.

Rape law assumes that consent to sex is as real for women as it is for men. Privacy law assumes women in private spaces have the same privacy as men do. Obscenity law assumes that women have the same access to free expression as men do. Equality law assumes that women are socially equal to men.

The UN Secretary General’s 2006 in-depth study on violence against women emphasized both the necessity and insufficiency of a purely legal approach to address the problem. The study stated that whilst laws provide an important framework for addressing the problem in establishing the crime, these need to be part of a broader public effort, which embraces public policies, education and other services.

Perhaps most notable in this context is the #MeToo movement. The movement has accomplished something that sexual harassment law has yet to achieve. It is eroding the two biggest barriers to ending sexual harassment in law and in life - the disbelief and dehumanization of its survivors. The conversations around #MeToo can grow sexual harassment law, and transform the legal system as well.17

The conversations around #MeToo can grow sexual harassment law, and transform the legal system as well.

Where do we go from here?

Galtung contents that the “deeper right would be the human right to live in a social and world structure that does not produce torture.”18 To combat GBV, to uproot it, we need to move beyond mere elimination of violence, and to move forward a world where people of all gender, especially women and queers attain true equality and parity.

The 1960s saw the rise of a new consciousness for women’s rights and ushered in a series of changes that still have an impact today – pushing back against the conventional femininity and gender roles, GBV, equal pay and equal opportunity, reproductive rights etc. The monumental strides we made were glorious but incomplete.

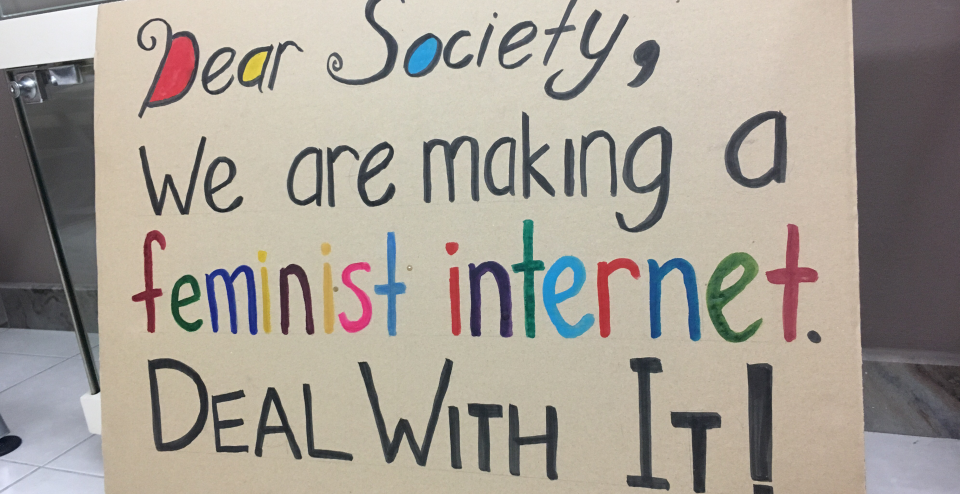

History is cyclical. Now once again women and queers, in all their diversity, are again galvanising the power of the internet to organise and mobilise, to take control of technology, to end GBV and to reclaim the online sphere as a safe space.

History is cyclical. Now once again women and queers, in all their diversity, are again galvanising the power of the internet to organise and mobilise, to take control of technology, to end GBV and to reclaim the online sphere as a safe space. We are at another momentous cultural shift to open the door even wider. Everything that we do - a tweet, a painting, an article, a conversation, a protest, a court case, a policy reform paper – they are all snap shots of an ongoing societal process of change and justice. Remaking the world and undoing the framework of oppression is a multi-generational process of imagining, creating, deconstructing and rebuilding. And there is no going back on what has been marched forward, and undoing of what has been heard and said.

And there is no going back on what has been marched forward, and undoing of what has been heard and said.

1.Galtung. J. (August 1990). Cultural Violence. Journal of Peace Research Vol. 27. No. 3. pp. 291-305. Return to main text

2.Kovacs, A., Padte, R. K., & SV. S. (April 2013) ‘Don't Let it Stand!’: An Exploratory Study of Women and Verbal Online Abuse in India. Internet Democracy Project. p.7. https://internetdemocracy.in/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Internet-Democra... Return to main text

3.End Violence Against Women Coalition (EVAW). (December 2013). New Technology, Same Old Problems. p.6 https://www.endviolenceagainstwomen.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Report_New... Return to main text

4.Aziz. Z.A. (July 2017). Due diligence and accountability for online violence against women. Association for Progressive Communication. p.5 https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/due-diligence-and-accountability-online-viol... Return to main text

5.Saint Martha’s Hall. History of Battered Women’s Movement http://saintmarthas.org/resources/history-of-battered-womens-movement/ Return to main text

6. Solnit. R. (2017). The Mother of All Questions. Canada: Haymarket Books. p. 22 Return to main text

7. Aziz. (2017). Op.cit. Return to main text

8. Penny. L. (March 2018). Who Does She Think She Is? Longreads. https://longreads.com/2018/03/28/who-does-she-think-she-is/ Return to main text

9.Association for Progressive Communications. (November 2017). Online gender-based violence: A submission from the Association for Progressive Communications to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. p. 18. https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/APCSubmission_UNSR_VAW_GBV.pdf Return to main text

10.Internet Governance Forum (IGF) 2015: Best Practice Forum (BPF) on Online Abuse and Gender-Based Violence Against Women. p. 33. http://www.intgovforum.org/cms/documents/best-practice-forums/623-bpf-on... Return to main text

11.Galtung. J. (1996) Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization Oslo, Norway: International Peace Research Institute; and London and Thousand Oaks; CA: Sage Publications. p. 30-33 Return to main text

12. The Women’s Legal and Human Rights Bureau (WLB). (March 2015). End violence: Women's rights and safety online: From impunity to justice: Domestic legal remedies for cases of technology-related violence against women. Association by Progressive Communications. https://www.genderit.org/sites/default/upload/flow_domestic_legal_remedi... Return to main text

13.Scales. A. (1992) Feminist Legal Method: Not So Scary. UCLA Women's Law Journal, Vol 2, Issue 0: p. 19-23. https://escholarship.org/content/qt7bv1j1pb/qt7bv1j1pb.pdf Return to main text

14.MacKinnon. C.A. (1989). Toward a Feminist Theory of the State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Return to main text

15. Scales. A. (2012). Op. cit. Return to main text

16. Aziz. Z.A. (2017). Op. cit. p.15 Return to main text

17. MacKinnon. C.A. (4 Feb 2018). #MeToo Has Done What the Law Could Not. The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/04/opinion/metoo-law-legal-system.html Return to main text

18.Cited in: Catia C. C. (July 2006). Galtung, Violence, and Gender: The Case for a Peace Studies/Feminism Alliance. Peace & Change. Vol. 31 No. 3 : 333 - 367. p. 338 Return to main text

- 13766 views

Add new comment