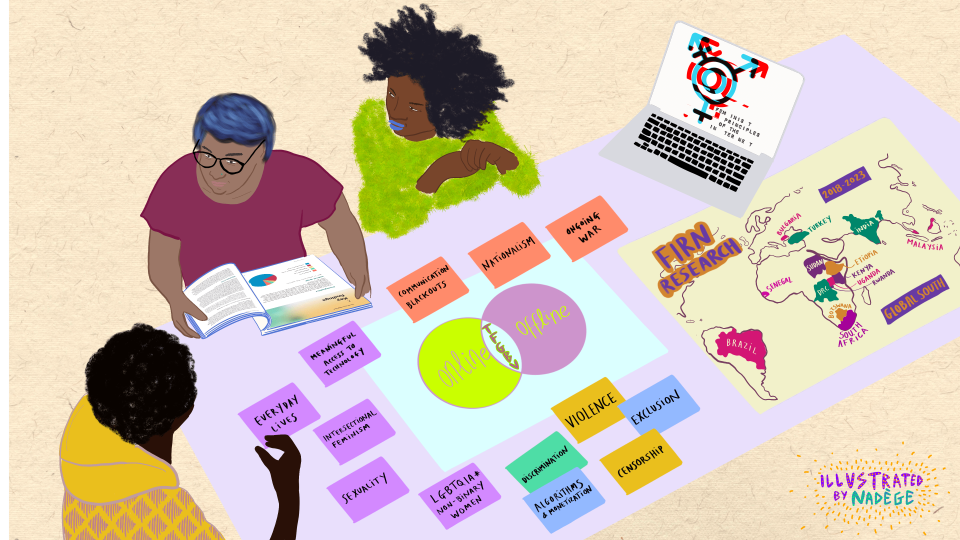

Illustration by Nadege for GenderIT.

Over the years, with the support of growing feminist internet research, expanding awareness of experiences, and ongoing advocacy from feminist technology groups, we are seeing a broader recognition of online gender-based violence (OGBV) and its impacts, its many variations, and how it manifests as a continuum of other forms of gender-based violence. One monumental case was, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women that was released in June 2018 with a thematic report that looks at “online violence against women and girls from a human rights perspective.”[1] And most recently, in October 2022, in a run up to the Sixty-seventh session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW67), there were deliberations on “Innovation and technological change, and education in the digital age for achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls.” As part of this, the expert group primarily addressed what they have referred to as online and technology-facilitated gender-based violence and discrimination and protecting the rights of women and girls online.[2]

These deliberations, other similar historically monumental events from before, have significantly contributed to the mainstreaming of the experiences of online and technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV). However, it is important for us to continue investing time and energy to understand the impact of TFGBV, the knowledge gaps that still exists, and limitations in legal and non-legal frameworks to support such cases and create a safe internet to everyone. In our two decades of work, at Association for Progressive Communications, it has become increasingly urgent to build better intersectional understanding of experiences of TFGBV.

One of the global shifts we are seeing at this moment is the wider usage of a variety of terms under which we understand online gender-based violence (OGBV). For instance, many organisations have pivoted to using the term “technology-related violence against women” or “technology-facilitated gender-based violence” (TFGBV). In a previous paper,[3] we argued why irrespective of the terms being used, our understanding of OGBV and TFGBV must be rooted in the importance for us to assess how online spaces and contexts continue to mirror the gender imbalance or the hierarchy and power we see in the offline space.[4]

In addition to this, the feminist research conducted within the Feminist Internet Research Network[5] (FIRN) provides us with critical Global South feminist perspectives and a prioritisation of context-based analysis that provide much needed nuanced views into the national and regional experiences of TFGBV, which then brought important reflections on rebuilding safer spaces online within a system that seems to not work for so many people.

In the past five years, several national and multi-country research projects have been conducted with support from FIRN. Out of the different research projects that FIRN funded and facilitated, research on online gender-based violence (OGBV) has been conducted in Brazil, Bulgaria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, South Africa and Uganda, online gender-based violence for LGBTQIA+ folks from Turkey and transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse folks from Uganda, Rwanda, South Africa, Botswana; experiences of online violence linked to freedom of expression and association in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Malaysia; and how access to technology is connected to online violence in Sudan.

The feminist research conducted within the Feminist Internet Research Network (FIRN) provides us with critical Global South feminist perspectives and a prioritisation of context-based analysis that provide much needed nuanced views into the national and regional experiences of TFGBV.

These research projects covered important themes such as: (a) insights into how the priorities and economic logic of algorithms have inevitably led to the amplification and monetisation of OGBV; (b) highlighting both the everyday and structural experiences of violence online, and bringing forth feminist discourse on language and technology through an intersectional exploration of race, gender and sexuality; (c) establishing the connections between experiences of online violence and lack of meaningful access to technology; and (d) mapping the complex journey of reversing anti-gender rights attitudes through the use of information and communications technologies. These works have provided us significant shift in our understanding of technology facilitated gender-based violence but has also enriched our understanding of the role contexts play in furthering violence, datafication, privacy, gendered disinformation, and organised circulation of homophobic, anti-gender, racist content online.

In this FIRN edition, we have focused on unpacking the impact of internet and digital rights from an intersectional feminist perspective and everyday realities of individuals and communities. We specifically focused on OGBV that continue to be largely invisible in the context of advocating for safe and secure access to the internet. Our previous research experience has also shown that the discourse of violence in the online sphere is not much discussed in feminist studies of gender based violence, nor do the connection between gendered structures of power that exist online and on-ground. Thus, we called on feminist researchers from the global south to critically research and explore OGBV against women, LGBTQIA+, gender diverse and queer people. The overarching research objectives are:

-

To provide an insight into the absence of OGBV from the feminist discourse of understanding violence against women, and reflect on the existing gap from the perspective expanding feminist politicisation of violence against women;

-

To tap into our existing network and work with feminists from Global South, to address the geopolitical and contextual understanding of online gender-based violence in the field of internet research from a feminist perspective more broadly;

-

To establish a Global South-South conversation and collaboration between feminist researchers with the aim of strengthening and growing the interest in exploring and deeply understanding multiple levels of gender-based violence in the digital spaces.

Feminist Research Methods to Interrogate TFGBV

We have funded four projects that are radically invested in feminist research methods, theoretical framework, ethics to understand and critically analyse OGBV. Each project has a clear methodological structure that centers research partners, pays attention to power dynamics between researcher and research participants, interrogates researcher’s positionally, questions familiarity and tries to read beyond linear analysis, and most importantly continuously checks ethical encounters with an active willingness to change course. In this editorial, we have put together executive summaries of the finding of these four research projects; the researchers synthesise and tell a story of their research journey and the feminist knowledge they have produced briefly, but we encourage our readers to visit the FIRN website (firn.genderit.org) to read and engage with the full research report.

Overall these four research projects have managed to address how, similar to elsewhere in the world, women, LGBTQIA+, and gender diverse people are silenced and denied access to a safe and secure internet due to misogynist and targeted harassment and violence. These researches have shown that marginalised groups face such harassment and violence on account of their gendered identity, sexuality or gender expression or their race, ethnicity, religion, political views etc. They have also highlighted how violence can be exacerbated based on ongoing conflicts and nationalism in the locations/regions.

Overall these four research projects have managed to address how, similar to elsewhere in the world, women, LGBTQIA+, and gender diverse people are silenced and denied access to a safe and secure internet due to misogynist and targeted harassment and violence.

The research projects in Turkey, Uganda, Rwanda, Botswana and South Africa primarily focus on a critical feminist exploration of OGBV against and within LGBTQIA+ communities. Part of the uniqueness of these projects was that it was led by members of the community. This played a role in expressing deep-seated structural violences that are more clearly seen by insiders; it was also easier to build trust and relatability with research participants, and to provide a more pragmatic and nuanced views of feminist ethical practices and care throughout the research.

The research projects in Sudan and DRC critically looked at experiences of women online with an expanded understanding of OGBV by challenging the narrowed views of what counts as technology violence. The research pushes the limits of online violence discourses by showing interlinked and layered power structures against the most marginalised. Similarly, both researchers from Sudan and DRC considered themselves as insiders due to their national identity but were critical of class and ethnic differences. The researchers paid particular attention to how structural violences, such as conservative cultural values, ongoing war, and regional conflict and instability exacerbate the experience of OGBV overlapping role of violence offline-online, and consequentially impacting women’s lives.

The following are important feminist knowledge and lessons that we hope to share with readers.

Nationalism’s ties to experiences of TFGBV

Time and again across the globe, history has shown us how discourse around nationalism is tied in neatly with exclusionary systemic structure that defines who can be part of the organising around nation-states, while simultaneously denies space for women and LGBTQIA+ communities. This means then basically the nation-state structure is built by men and hetero-patriarchal socio-cultural values; thus, inflicting violence on those who don’t fit into these narrow ideas of nationalists.

Looking at the connections between nationalism and women’s rights, Magda Shahin and Yasmeen El-Ghazaly argue that the ‘woman question’ becomes relevant in how people define and defend a nation. They write, “Female activists became ‘mothers of a nation’ with a special nurturing and protective mission... Just as ideals about women’s and family honour influence ideas about the nation, ideals of masculinity have played a role in shaping the nation and are in turn influenced by nationalist ideologies.” Research findings in FIRN, from different country and region context, have shown that such kinds of sentiments are one of the catalysts to the continuation of online violence targeting individuals and communities that seems to directly or indirectly threaten androcentric nationalist ideologies. With an increasing instability and war in different parts of the world, we are also witnessing how governments use different technologies to sustain their power by masking nationalism as a strategy to silence and exclude those that challenges the state.

The existence of these nationalist ideologies are immediately found embedded in cultural and moral values; particularly attacks on women in politics,[6] women in journalism,[7] and women human rights defenders,[8] and attack on LGBTQIA+ individuals and their presentation and expression of gender and sexuality.

With an increasing instability and war in different parts of the world, we are also witnessing how governments use different technologies to sustain their power by masking nationalism as a strategy to silence and exclude those that challenges the state.

Interestingly, in most of the research studies conducted by FIRN partners, we see the implicit and explicit connections being made between nationalism, violence against women and LGBTQIA+ persons especially within online spaces. For instance, a trend was found between political hate speech and the rise in violence against the LGBTQIA+ community in a recent research conducted by KAOS GL Association in Turkiye.[9] They write: “The anti-LGBTI+ propaganda of the Islamist and the nationalist party manifests itself in the answers of our participants. There are four main claims forming the basis of their hostile attitudes: The first is that the queer community has come together to destroy the concept of family. The second is joining forces with the increasing global anti-LGBTI+ propaganda. The third one is hampering the opposition from doing progressive politics. The last and the most important one is slowing down the queer and feminist activism, which stand out as the most powerful opposition force against the Turkish government.”

Similar sentiments are often mentioned in different countries and regional contexts as well; the recent Ugandan anti-gay bill emerged from the same rationalisation - destroying the family and unAfrican. The connection we need to make here is that, these anti-human rights laws and hate speech conducted at a state level energise, give permission, and justify actions of individuals and communities that are homophobic to continue the attack in online and offline spaces in the name of duty to one’s country. In addition, the feminist research in Sudan and DRC have also shown how nationalism and its rhetoric have been radically impacting women from freely accessing online spaces. The research in Sudan shows how the marginalisation of women is infused in the very idea of national identity and cultural values to an extent that, in some cases, women get killed for simply accessing internet and being online. Meanwhile the research in DRC shows that women politicians, journalists and government officials still struggle to secure their freedom of expression due to the attack they experience by patriarchal and misogynist men who feels its their responsibility to discipline women to abide by the androcentric state structure, and from freely exercising their citizenship rights publicly. These context-based feminist analysis point towards the fact that integral part of the continuation of TFGBV is embedded in nationalist rhetoric that is masculinist, misogynist, homophobic, and radically patriarchal, which validate online violence and make use of these frictions to sustain political power dynamics and violent systemic structure that continue to further marginalise women and LGBTQIA+ citizens.

Online and offline violence are connected

All four research studies show us the ways in which political hate speech and gendered disinformation impact the levels and experiences of violence online by those belonging to gender marginalised and diverse sexualities’ communities. For instance, the Left Out Project focused on the online violence experiences of trans, non binary and gender diverse persons belonging to four countries in Africa: Botswana, Rwanda, South Africa and Uganda. Their research confirms these experiences of violence and further suggests that online experiences of violence are deeply connected to and further experiences of offline violence of these groups. The research explores this connection, and one participant of the research shared: “Yes, that [moving from online to offline] has happened, where you would have a conversation with someone on Facebook and then it moves and then eventually you meet somewhere, and they continue being that perpetrator. It’s traumatising, it goes from being an online encounter, and you are sort of protected by the internet because they're not in front of you and suddenly, they're in front of you. That becomes really, really dangerous in that space.”

The research in Sudan shows how the marginalisation of women is infused in the very idea of national identity and cultural values to an extent that, in some cases, women get killed for simply accessing internet and being online.

These connections further what feminist researchers have been observing and reiterating from the beginning with regards to online violence being an extension of the gender-based violence faced offline, and to “avoid seeing this violence as a binary between online and offline violence, which often furthers the perception that online violence is distinct and separate from systemic gender-based violence.”[10][11]

The research done in Sudan amplifies our understanding around the connections between offline and online violence – where we see experiences of violence against women magnified when there is an attempt to improve women’s access to resources via the internet. The researchers write, “Women’s struggle with online GBV in Sudan showed a link between challenging the status quo and experiencing offline violence as a result of these actions. The FGDs showed that offline violence in such cases can be divided into two, domestic violence and violence by community members whose actions of violence are either justified by the social norms or these actions may or may not be incited by the digital campaign against the victims. The justification of violence against women using social norms and the possible incitement could amount to gender-based hate speech.”

These studies ascertain the ways in which we need to shift, expand and deepen how we see the impact of violence in digital spaces and its deep rooted connections to violence experienced onground - sometimes a continnuum of offline violence, and other times violence and patriarchal control offline resulting in lack of access to digital worlds. Thus, our attempts to understand TFGBV must include this diversity of experiences and cater to the lived experiences of women, trans and non binary people whose contexts determine their individual and collective experiences of the digtial world.

TFGBV and freedom of expression

In many countries with repressive regimes and conservative societies, social media and the internet were seen as path-breaking for freedom of expression. The Global Expression Report of 2022[12] reported that there were 5 military coups in 2021 of which 4 were in Africa. One of them was Sudan, which is of particular importance in this context because of the ongoing political turmoil, violence and exodus from Sudan. The report spotlights the series of impacts on freedom of expression within Sudan because of the ongoing crisis. In the research, one of the observations around digital experiences of women in Sudan was connected directly to the impositions of internet shutdowns. Women lose opportunities, income and access to resources in these circumstances because of long drawn communication blackouts. Though these experiences are noted as infringing the rights of women in Sudan, this research provides us with ample opportunity to broaden our perspectives, beyond wicked problems of sexual harassment, hate speech, trolling etc, on how technology-facilitated gender-based violence is often enacted through complicated national and global structures, such as sanctions against Sudan by the international community, that deny or restrict women’s access to technology and any freedoms possible therein. This phenomenon is existing on top of the social and cultural restrictions that women struggle through in a conservative and religious society such as Sudan. Using intersectional feminist analytical approach, the research demonstrated how women were hesitant to participate and freely express themselves online because they could be labelled as ‘undisciplined’ and ‘have no guardian’.

These studies ascertain the ways in which we need to shift, expand and deepen how we see the impact of violence in digital spaces and its deep rooted connections to violence experienced onground - sometimes a continnuum of offline violence, and other times violence and patriarchal control offline resulting in lack of access to digital worlds.

The fear around their freedom of expression was similarly tied to access and patriarchal control for participants in the research conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) by Core23Lab. The participants shared within this research that many of the women’s husbands controlled their access and use of technology by framing it as “a waste of time” and “not important for women”. Thereby restricting their avenues for access to information, freedom of expression and association – while relying on their husbands to not only decide when to use the digital devices but also how. However, the research also noted that women in DRC felt far more comfortable sharing their opinions and speaking to each other in closed WhatsApp groups vs public forums because of the fear of repercussions of expressing their opinions freely online, and therefore self-censoring to protect themselves.

Though the research participants in DRC and Sudan have shared different ways they use to navigate the social, cultural, political, and economical hurdles from accessing the internet, they are still affected by the limitations of freedom of expression imposed on women online, and the violence that they face on the online spaces emanating from cultural or political repressions. Both research indicate that there is still a huge gap in terms of addressing women’s equal human rights that is surfacing through the gender based violence women are experiencing on the internet. It is also important to understand that TFGBV as a lived experience intersects with bodily autonomy and the right to self-determination of women in their day-to-day lives.

As a concluding remark, and as a way of sharing our gratitude to our partners, we like to spotlight specific experiences and political shifts that have happened during this research cycle, which resulted in challenging us to enrich our collective goal for a feminist internet in the global South. Turkey experienced a massive earthquake which resulted in the displacement of many communities. Soon after, the country also went through a national election period. Our research partners, therefore, have used the research findings to advocate for the LGBTQIA+ communities while at the same time challenging government officials to consider the policy recommendations that the researchers have provided, and to inform the Turkey LGBTQIA+community to make informed decisions regarding their vote. In another context, on April 2023, Sudan went through a devastating war that is active at the time of writing. Our research partners were personally affected by this war. While going through such a national nightmare, our partners have used the research project as a space and tool to communicate about violence against women and violence online that is being used as propaganda by the warring parties, diaspora community, and international entities. Additionally, Uganda, one of the countries that the Left Out Project explored, has signed the anti-homosexuality bill which directly and violently affects the LGBTQIA+ community in the country. Last but not least, our research partners in DRC have indicated that although there is no active conflict and war in DRC, particularly at central cities, the reminiscences of conflicts from the recent past still have a tremendous impact in how people experience their everyday lives.

We are mentioning these historical occurrences in the context of this research collaboration and this editorial because we want to show how the constellation of these projects forced us and our partners to shift our thinking around the political meaning of “researching violence” against marginalised communities and individuals from a feminist intersectional perspective. We were challenged and encouraged to push the limits of our imagination of OGBV by paying witness to how structural violences at a national level hugely impact the most vulnerable and already marginalised individuals and communities; and how, almost simultaneously, an extension of such a crisis is violently communicated on the online spaces.

It is then, from an intersectional feminist perspective, dwelling on the issues that restrict women’s and LGBTQIA+ communities' self-expression using different online platforms can only be understood through the analysis of how different hetropatriarchal social orders impact the algorthmic design, and hence they ways in which it amplifies the friction that exists for women to be online and express themselves and their ideology freely.

It is then, from an intersectional feminist perspective, dwelling on the issues that restrict women’s and LGBTQIA+ communities' self-expression using different online platforms can only be understood through the analysis of how different hetropatriarchal social orders impact the algorthmic design, and hence they ways in which it amplifies the friction that exists for women to be online and express themselves and their ideology freely. This is to say that technology doesn’t happen or get created in a vacuum, it is rather influenced by such social and moral codes that eventually perpetuate the repression of marginalised communities.

This edition put together by Tigist S. Hussen and Srinidhi Raghavan caters to four such research projects conducted between June 2022 and July 2023. We write this editorial introduction from a position of a role that we have been playing as research lead and coordinator. Our reflection of the research journey with partners through our own learning and observation might not been a perfect representation of their work, but no representation is perfect anyway. We write because this is how we have been impacted by being part of the process. Through each of the individual pieces, we grow closer to understanding the need for research to be feminist, rooted in local contexts and experiences, and enabling the voices of marginalised communities to influence policy and advocacy. Such research brings us closer to building digital and on-ground worlds that are just, inclusive and enable the majority of us.

Footnotes

[4] Maskay, J., & Karmacharya, S. (2018). Online Violence Against Women: A continuum of offline discrimination. LOOM. https://taannepal.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Online-Violence-Against-Women-2018.pdf

[5] The Feminist Internet Research Network (FIRN) is a collaborative and multidisciplinary research project led by APC, funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and APC. FIRN focuses on the making of a feminist internet, seeing this as critical to bringing about transformation in gendered structures of power that exist online and offline and to capture fully the fluidity of these spaces and our experiences with them. Members of the network undertake data-driven research that provides substantial evidence to drive change in policy and law, and in the discourse around internet rights. The network’s broader objective is to ensure that the needs of women and gender-diverse and queer people are taken into account in internet policy discussions and decision making. https://firn.genderit.org

[9] To be released in August 2023

[10] APC. (2017). Online gender-based violence: A submission from the Association for Progressive Communications to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/APCSubmission_UNSR_VAW_GBV_0_0.pdf(link is external)

- 803 views

Add new comment