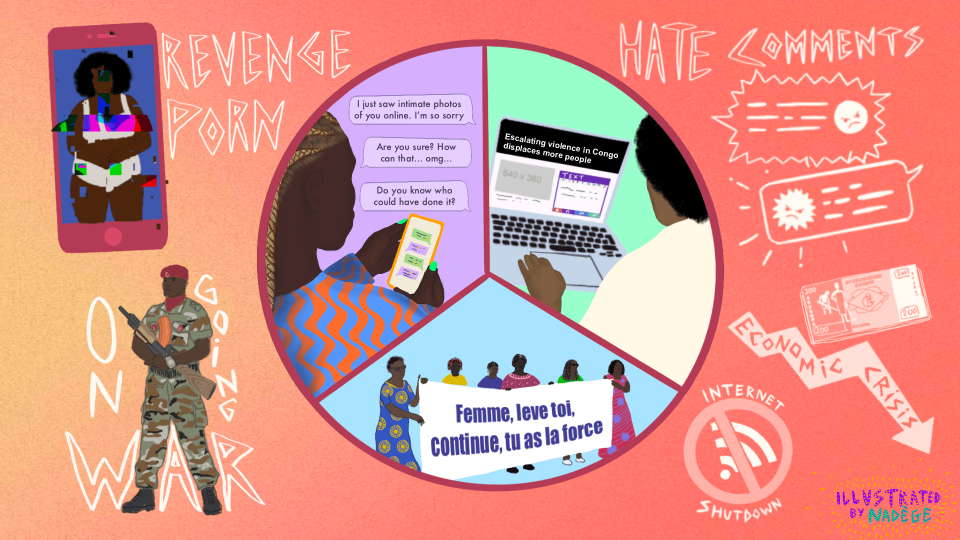

Illustration by Nadege for GenderIT

Executive Summary

A holistic perspective includes the human intrinsic and extrinsic factors of the victims’ painful experiences that affect their mental health, physical degradation, loss of reputation, and dignity when exercising Freedom of Expression (FoE) and Freedom of Association (FoA). A holistic approach is critical to developing a survival centered solution that allows power to rest with women over OGBV concerns. Especially in the digital age where the sum of the parts that impact an individual are often considered in silos rather than the whole. OGBV in this case carries a much more heavier effect overall, that is skin deep and it was crucial for this research to look beyond the normal scope that often comes to mind when one thinks of violence in efforts to develop interventions that address the matter in whole as it is in the lived experiences of victims.

In this digital age, social networks have been a gathering space for many. This has allowed different people to exchange on issues that affect the community, particularly socio-political and economic problems. In particular, rights such as freedom of expression (FoE) and freedom of association (FoA) as fundamental rights in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are guaranteed by the constitution of 18 February 2006, the country's supreme law.[1] In the case of DRC, gender based violence has been weaponised for many years as a tool of war and many women have been victims. While much needed efforts are geared towards the offline world, it's important to ensure that the digital aspects to gender based violence are well researched, understood and addressed in a holistic manner as they are a reflection of each other. In our efforts to understand the social dynamics of gender based violence we embarked on a mission to understand gender based violence but from an online perspective in relation to how it affects women exercising their rights such as freedom of expression and assembly on digital platforms.

As the number of internet users in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is increasing each year, this knowledge gap becomes a crucial component to defining a holistic internet health for the DRC. It is reported that by January 2022 there were 16.5 million internet users, which is roughly 17.6% of the country’s population.[2] However there is a lack of gender disaggregated data when it comes to technology adoption, including the statistics on the number of internet users. While the growth is slower for a country that is the second largest in Africa, government hindrances have limited this growth through their culture and practice. This coupled with the ongoing humanitarian crises that the DRC has experienced for several decades have had several repercussions on the social life of the populations of the affected regions in general, but with an impact on women's rights in particular, especially by amplifying sexual and gender-based abuse and violence. Abuse of power and gender inequalities have exacerbated women's vulnerability to all these forms of violence and have significantly reduced women's ability to speak out on "sensitive" issues within communities strongly dominated by sociocultural and patriarchal norms.

For nearly eighteen years the country has being marred with human rights violations including silencing dissent by stifling civic spaces such as the digital civic spaces through internet shutdowns since President Joseph Kabila Succeeded his father President Desire Kabila following his assassination. As a result the digital sector in the DRC was more or less governed by a reasonably general legal framework full of inadequacy regarding the concepts covered in the law with the evolution of digital technologies. Still, this legal framework did not respond in a relevant way to human rights violations or to the impunity of those who violate them. These rights include those of women and girls on the Internet.

While much needed efforts are geared towards the offline world, it's important to ensure that the digital aspects to gender based violence are well researched, understood and addressed in a holistic manner as they are a reflection of each other.

The overall objective of the research was to understand the existing inequalities that hinder women from fully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and assembly on the internet, identify measures for redressal, and propose policy changes that ensure maximum exercise of these restricted rights, and protection of women in the online space. In addition, the research sought to close the knowledge gap on online gender-based violence (OGBV), and encourage women’s participation in the technological field in the DRC. Further, the research explored and analysed the social impact of digital technologies on women and girls, surfaced policy and human rights-related issues in digital technologies, with particular focus on OGBV, and investigated the effects of digital violence on the governance system.

Methodology

For this research to understand how OGBV affects the way women interact online, especially for FoE and FoA, we had to employ mixed methods and learn from previous research done in the DRC to identify the best way to get information. Our research led us to include a diverse group for interviews, surveys and focus group discussions (FGDs) to help us gain more insights. This included looking at how ordinary women internet users are affected by OGBV. The survey questions were distributed in French while the FGDs and interviews were conducted in a mixture of Congolese Swahili and French.

We conducted research through surveys that were filled by 100 women between the ages of 21 and 40, representing Tanganyika, Lualaba, Katanga, Kasai, Lomami, Kinshasa, Kwilu and Kivu regions. Some 28 participants were from ongoing conflict areas of Goma, Kivu and Bukavu in the eastern part of the DRC. The surveys helped us to gain insight on key issues such as their understanding of OGBV, how this affects FoE and FoA for women, which platforms did women experience the most violence on, which kinds of violence and how this affected their behavior online.

We also conducted focus group discussions to delve deeper into understanding how OGBV was experienced and how it affected different groups of women. In this instance we looked at women human rights defenders, women activists, journalists and the everyday woman. We conducted this with groups of 6-8 women from the 5 different provinces with a total of 24 women and also had in depth interviews with about 30 women who mostly consisted of university students, journalists and women human rights defenders/activists. Our methodology employed the feminist principles and made use of more particularly how digital platforms like social media amplified and played a role in movement building for women in the DRC and how this in turn led to OGBV as a backlash and vise versa.

Research Findings

Over 88% of respondents indicated that women in the DRC face significant violence when exercising their right to expression and assembly online, leading to a culture of self-censorship. During war, women who tend to write about the situation on the ground fear that exposing their profiles and information on social media platforms leaves them easily vulnerable to be attacked both physically and emotionally.

In terms of which groups were most affected by this violence, women politicians and community leaders, women’s rights activists, journalists, and students were seen as those at the receiving end of violence. Journalists were often attacked for their work, which involves publishing online posts and interacting with their audiences. Activists, on the other hand, were targeted because they often speak out on behalf of their communities and are often bullied; and students because most are perceived as being “naïve" and easily targeted so they fall victim to harassment and blackmail online. In addition, women politicians were attacked to dent their reputations and such attacks increased during election time.

While we did not get to interview women politicians, an analysis of some notable women political figures' social media accounts brought some interesting findings. We learned that women politicians who use platforms such as Twitter to communicate their work face backlash especially from men but surprisingly, some of the abusive responses came from women. This shows that although most perpetrators of OGBV are men, women also use the space to intimidate other women.

Journalists were often attacked for their work, which involves publishing online posts and interacting with their audiences. Activists, on the other hand, were targeted because they often speak out on behalf of their communities and are often bullied; and students because most are perceived as being “naive" and easily targeted so they fall victim to harassment and blackmail online.

During election campaigns in DRC, more women politicians find themselves victims of OGBV as they face targeted comments, abusive content and trolling, among others. For women politicians in the DRC, social media platforms are not only a means to share their work but are also avenues to advocate for pertinent issues and push for more women’s participation in politics. Currently, women constitute 52% of the population but their representation in Parliament is a mere 12.8%, which puts the country well below the average parliamentary participation of 24% in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite laws introduced by the Congolese government to promote women's participation, including adding the principle of equality between men and women in the preamble during the revision of the Constitution on 18 February 2006,[3] women still have more barriers to fully utilising their rights to FoA and FoE.

The research found that:

-

Women journalists are often trolled, bullied, body-shamed, and worse, attacked with malicious comments on their social media accounts. They are also the group that make use of digital platforms the most to communicate their work and build their portfolio.

-

In a country that witnessed vast violations of human rights, especially in the east, a group of women human rights defenders and activists that were interviewed in Goma said that OGBV often comes from well-known political entities, and they often find themselves at a crossroads with political figures as well as perpetrators of human rights violations. They use their rights of FoE and FoA for movement-building as well as advocacy. However this often comes with both physical and online threats. This group often faces cyber harassment, trolling and cyberbullying; sometimes this is coupled with manipulated images.

-

Our study found that a majority of everyday women internet users in the DRC are subject to non-consensual use of intimate images (commonly referred to as revenge porn), cyberbullying and unwanted sexual advances, mostly on social media platforms. Some 64% of the respondents said the platform where they faced the most violence is Facebook where crimes like identity theft are rampant. Responses of participants suggest that they do not have a clear definition of what OGBV really is.

While some positive strides have been made in the legal and policy landscape such as the amendment of the Constitution of 2005 through 2011 on human rights, of fundamental freedoms, and of the duties of the citizen and the state, the revision of Law No. 96 of the Constitution which safeguards freedom of expression in both offline and online media, however, is still problematic, especially regarding the internet and online access for actors. Most respondents were not aware of legal provisions that protect freedom of expression and safeguard against violence, in particular in the online space, and this situation has created insecurity, especially among women.

The dynamics within the communities in the DRC, which are mostly patrilineal which allow men to have more power to voice their needs and practice FoE and FoA, unlike women in their communities have also played a crucial role in limiting women’s online and offline participation. For most women in the DRC, OGBV is still a new and not fully understood experience for them to understand its implications on their basic rights of freedom of expression and association. Gender-based violence is often tied to systems, practices, norms and cultures that exist in communities. This is the same case for the DRC where the culture, despite some communities being matrilineal, supports and perpetuates GBV by silencing the voices of women and giving more power to men.

In such cultures and systems that favor men's access to key rights such as FoE and FoA over women, it is difficult to address OGBV without first dealing with the cultural and societal norms of oppression. Most often, GBV is looked at from an offline perspective, specifically the physical abuse such as rape, domestic violence, etc. and is hardly looked at by the sum of its parts. Hence, the methods used to address the challenge tend to be in silos. The relationship between offline and online GBV demonstrates the need for mechanisms that are able to look at it in a holistic way, keeping in view that the online world is just a reflection of the offline world.

In light of this, we learned that most women in DRC do experience OGBV but were unable to identify it as OGBV when they experienced it due to the knowledge gap; however, they did know how it made them feel. As a result most chose to self censor and some all together withdrew from using such platforms. Despite how enabling the social media platforms are and how most of the women expressed productive use of the digital platforms for matters such as business, entertainment, learning and communication, there was limited use of online platforms for civic participation. This is also tied to the fact that access and control of technology (within households?) is mainly male-dominated; hence women miss out on the digital revolution, especially due to device and affordability gaps.

Gender-based violence is often tied to systems, practices, norms and cultures that exist in communities. This is the same case for the DRC where the culture, despite some communities being matrilineal, supports and perpetuates GBV by silencing the voices of women and giving more power to men.

In areas of conflict, access was not prioritised, especially since most women had more pressing matters such as safety and basic needs to be concerned about, and cost of access was also very high in terms of devices hence many couldn't afford to get connected in the first place. The knowledge gap of identifying OGBV when it happens is also tied to how to respond when it does or in the least prepare for it, in this case most women didn't have enough skills to prepare, prevent or respond to OGBV. Despite the presence of laws on general GBV, there are no specific laws that address OGBV in itself, though general cybersecurity provisions exist; however, most women do not know how to negotiate such laws.

Recommendations

Legal reforms: The current legal provisions and frameworks on violence against women are not sufficient to safeguard women online. Furthermore, there is a knowledge gap among judges and lawyers on how to prosecute on such matters, hence the need for more capacity building.

Awareness raising: Addressing online violence in the DRC will require different stakeholders such as government and CSO’s to deliberately take up the initiative of bridging the knowledge gap among women on OGBV so that they can be able to identify, prepare and respond to OGBV when exercising their rights on social media. The various technology platforms should agree to a mechanism for prosecution of wrongdoers to complement digital security practices. Ideally making it easy for women to have the courage to speak out, seek and receive justice.

Role of social media platforms: Social media platforms have a huge role to play to ensure they facilitate free expression and that no one quits, by implementing mechanisms to fight against online harms, especially those targeted at women and girls

Digital security training: Digital security training was cited as critical for women, particularly journalists and human rights defenders. This is because most of the respondents we interviewed did not have an idea on how they can stay secure online and which avenues they can use to reclaim their power when exercising their rights in the digital space.

Movement building: feminists and women’s right defenders must extend their offline GBV work to include online GBV advocacy, especially using digital tools as a means of communication to those already using online means. Discussions with women activists and human rights defenders brought to light that the DRC has mechanisms in place to educate and respond to GBV, but not OGBV. There is a need to build movements around OGBV.

Holistic approach: The government and other stakeholders should take a holistic approach in developing solutions that address OGBV by factoring in cultural practices and structural and systematic causatives. This will be crucial to developing a survival-centered solution that allows power to rest with women over OGBV concerns.

Finally, shifting power from the systematic and structural barriers that have long existed in the communities in DRC towards GBV and more so OGBV will require building resilient women who will not only adjust to the ever-evolving tech space but also be able to build movements and amplify their voices using the very tool that is currently being used to suppress their voices. For OGBV’s impact on FoE and FoA to be mitigated, it is important for knowledge gaps on key digital skills such as security to be imparted to women and their capacity improved to identify, anticipate, prepare, prevent and respond to OGBV.

[1] Femnet.org, Participation Policy of Women in the Republic Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) https://femnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Policy-Brief-WPP-DRC-French.pdf (Consulted on May 04, 2023)

[2] Kemp, S. (2022, 15 February). Digital 22: The Democratic Republic of Congo. DataReportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-democratic-republic-of-th…

[3] FEMNET. (2021). Document d’orientation sur la participation Politique des Femmes en République Démocratique du Congo (RDC). https://femnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Policy-Brief-WPP-DRC-Fren…

- 242 views

Add new comment