Illustration by Rawand Issa for GenderIT.

[Written by Habash, co-edited by Che-GPT]

Half of my waking hours are spent by me talking to myself, with internal voices that sometimes mimic my father's tone and sometimes my mother's. At other times, a collage of various tones resonates within me.

With help from my psychiatrist, I succeeded in silencing my father's voice. I have softened its firmness and have subverted its philosophy that celebrates masculinity and attributes self-proclaimed "values" to it. I thought my mother's voice didn't do any harm, since it rarely echoed in my mind. However, I later discovered that softly and tenderly, it folded my father's voice into my mother’s gentle tone.

During his work journeys abroad, my mother had to replace my father. She had mimicked and incorporated his philosophy into my upbringing, echoing the same firmness but with a tone of care and attention. This had masked her strictness in my memory to make her voice more elusive within me.

After years of trying to silence my mother's voice, I believe I have been successful, so my inner chamber is completely evacuated for my voice—a voice of me as a child bullying me as a grown up.

Had my mother's gentle voice given legitimacy to her resolute voice, making it easier to sneak into my mind, claiming it as mine and discarding it as hers?

Until very recently, I didn’t succeed in getting rid of this voice. It continued to blame and mock me, and all attempts to converse with it have failed, following my doctor's advice to “re-parent this voice” and to "try imposing my respect on it." The textbook advice that never works. However, I have learned that dealing with it as a child, without any of us having the upper hand, without imposing rules upon it in exchange for freeing me from its own rules, is a way to calm this voice down.

Feminist or a feminine patriarch?

Perhaps I am one of those people who simply need feminism. I have experienced the inflated masculinity, at school, at home, at university, at work, in the company of friends, in the expectations of my parents and of past lovers. I am the one afflicted with chronic depression, the skinny, with a soft voice in his adolescence, who “lacks any sense of humour” according to the standards of the vulgar sexual jokes, the one incapable of donning the attire of bullying as comedy and carrying them in a mocking carnival targeting a weaker male, leading him to a stage and comment on him with a lighthearted voiceover, ready to swiftly mock, even, his clown’s groaning by making a quick and rare witty remark, with a dead heart.

Until very recently, I didn’t succeed in getting rid of this voice. It continued to blame and mock me, and all attempts to converse with it have failed, following my doctor's advice to “re-parent this voice” and to "try imposing my respect on it." The textbook advice that never works.

Therefore, I will not hold back my dismay at a feminism that does not fundamentally differ from masculinity. Dismay at women executives who have gotten promoted in cultural institutions, empowered to say in their meetings, "We will not collaborate with so-and-so because I heard they have severe depression." The ones proud of their positions, who claim gender balance in their institutions despite managing them with the same masculine values, with inflated egos and strictness. Those who choose to grant opportunities to homosexuals, bisexuals, and transgender individuals in order to say, "Find a job that puts bread on your table instead of trying to work in the arts." These women are feminine patriarchs, branded by one or another institution, moulded by the simulacrum-producing machines.

One example of the feminine patriarch is Martha in the film "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf". In the film, Elizabeth Taylor portrays a domineering woman who turns her husband's life into hell. Humiliation and open betrayal, relentless exposure of his vulnerabilities, constant reminders of his inadequacies, as if she replaced the patriarch in the form of a woman. With this substitution, a frightening interpretation of Virginia Woolf's is realised, negating the feminist values brought forth by Woolf herself.

Unlike the defined structures that created Martha in the era in which the film/play was created, Martha of today’s world is being produced by more liquid tributaries: the tributary of political correctness and identity politics imposes identities on everyone and leaves them with wooden swords in a defensive performance, an enforced role not so much different from the gender roles criticised by Judith Butler.

There is also the tributary of capitalism, which requires representative simulacrums embodied in shining women who can be marketed as products, registered brands for one discourse or another. This tributary reaches the Arabic-speaking region, filtered through authoritarian ruling systems, creating distorted and regressive versions that fuel authoritarianism and whitewash it with false claims of women's empowerment. This has produced, in Egypt for instance, thieves and ministers who openly express their desire to slice critics.

Additionally, there is another tributary fueled by feminist currents such as carceral feminism, with its necropolitics, which, in the Egyptian context too, breathes life into patriarchal practices exercised against women inside prisons, where they are subjected to invasive searches with black bags worn on hands, and transgenders who are detained and imprisoned in binary-gendered cells without protection.

Another contributing tributary to the creation of the feminine patriarch is left-wing ideologies, as it reproduces representative democracy by choosing symbolic representatives to lead the opposition, heavily relying on the issue of consciousness. The conscious masses, who read, discuss, and think, remained a dream that various left-wing currents sought to achieve, giving the green light to the "conscious ones" to steer towards this dream, allowing decision-making power to be concentrated in the hands of small groups who easily can be substituted and devalued by capitalism, or excessively burdened with signifieds by the same currents that produced them, waiting for the full vessels to overflow into emptiness in the latter case, and for the emptiness to overflow even more in the former.

I will not hold back my dismay at a feminism that does not fundamentally differ from masculinity.

Amidst these tributaries, the current reality in the Western Asia and North Africa (WANA) region imposes a defensive role on many feminists against predatory societies and biassed patriarchal laws. They are also accused of extremism, a claim made by masculinists, who conflate it with radicalism, either out of awareness of advantages they are unwilling to relinquish, or due to a lack of awareness of the boundaries between self-defence and aggression. Indeed, feminists are not to blame for this, but this defensive role limits the influence of feminism as a theory that has broader dimensions beyond this role.

For block-feminism

Between the two models of the feminine patriarch and the feminist, blockchain technology and its applications intervene with rules that sometimes promote the emergence of the first model and other times nurture the second.

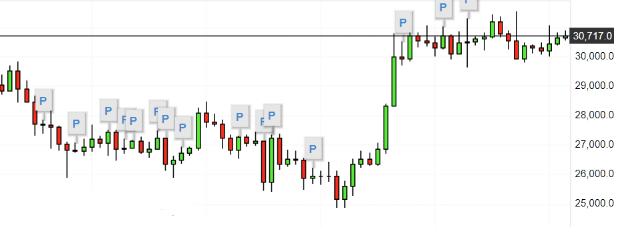

Decentralisation, horizontal systems of labour, and the abandonment of hierarchies are values that are inherently feminist. However, these values contradict patterns of masculinity inherited in the current applications of blockchain. The applications that seem revolutionary at the first glance, but with a closer look, it shows how it remains centred around something/someone. The proof-of-work algorithm used by Bitcoin, for example, centres around who owns more energy, and the proof-of-stake mechanism employed by numerous cryptocurrencies gives preference to those with more capital. Even the shape of the candles in the price charts of cryptocurrencies resembles a phallus figure, with everyone aspiring to reach the green-coloured of it.

The shape of the candles in price charts of cryptocurrencies resembles a phallus figure. Source: Investing.com

Therefore, I believe that blockchain and feminism both need each other. The practical application of blockchain is crucial because it creates an opportunity to put concepts into practice instead of merely debating them or, more precisely, alongside debating them. The debate that remains important but cannot stand alone. It needs support by actual implementation in a space that exists between reality and virtuals, providing an opportunity to experiment with and apply feminist values. This practice goes beyond feminism and extends to reshaping the blockchain itself, in a relationship where there is no fixed definition for the subject or the object, and each constantly exchanges roles.

This reciprocal relationship is embodied in the DisCo, the distributed cooperative organisation, a sibling to the Decentralised Autonomous Organisation (DAO), but with less enthusiasm for automation and individualism.

DisCos have been brought by a group of feminists, applying concepts of the feminist economics to substitute/tame game theory.

The DisCo Manifesto begins with the story of Russian chess player Garry Kasparov's defeat by the IBM computer Deep Blue in a chess game in 1997, a defeat that made Kasparov doubt its fairness, thinking that one of the 19 moves made by the computer resembled a human move rather than a machine's. This led him to believe that humans had assisted the computer during the match. The belief that was not proven, and later, was interpreted as a bug in the machine's code. This particular bug inspired collaboration between humans and machines in the form of centaurs that were capable of defeating computers much superior to Deep Blue.

Using the centaur metaphor, the manifesto calls for organisations to leverage the automation provided by blockchain while maintaining the human element, referred to as the bug, to guide them not by the compass of profit and growth but by the compass of social priorities, embracing ideas from feminist economics. This foundation is based on the added value to society, rewarding, for example, unpaid work related to childcare, collaborative relationships, and even pro-bono work.

Decentralisation, horizontal systems of labour, and the abandonment of hierarchies are values that are inherently feminist. However, these values contradict patterns of masculinity inherited in the current applications of blockchain. The applications that seem revolutionary at the first glance, but with a closer look, it shows how it remains centred around something/someone.

The DNA of DisCos consists of several essential elements. Firstly, it embraces commons, which are community-led, self-organised, peer-to-peer, non-hierarchical, and non-coercive social relations embedded within human networks. This foundation emphasises the importance of collective action and collaboration.

Another key component is Open Cooperativism, which focuses on locally grounded, commons-oriented cooperatives that are interconnected on a transnational level. These cooperatives prioritise social and environmental work, fostering a sustainable and equitable approach to economic activity.

Furthermore, DisCos incorporate Open-Value Accounting, a system of accounting that documents contributions to shared projects, enabling retrospective analysis of distribution. This ensures transparency and fairness in resource allocation.

Enveloping the above, Feminist Economics plays a significant role within DisCos, asserting value sovereignty and challenging traditional economic paradigms. By prioritising social well-being over profit and growth, DisCos acknowledge and reward unpaid labour, cooperative relationships, and charitable endeavours.

The integration of these principles within the framework of the DisCo offers solutions to the problems inherent in the current systems that perpetuate feminine patriarch models. By adopting commons-based production models and fostering feminist economics, DisCos create a space where values such as decentralisation, horizontal organisation, and the abandonment of hierarchies thrive. It provides an opportunity to practise and experiment with feminist values, bridging the gap between theoretical debates and real-world applications.

Moreover, DisCos can address the issue of tributaries, where power and wealth flow predominantly toward the privileged few. By redefining the guiding principles of blockchain technology and emphasising social priorities, DisCos enable the transformation of the economic landscape.

FemiGamism

DisCos have sparked my curiosity about what game theory could lead to if it is applied in them. The dominant presence of game theory in existing blockchain applications makes me wonder if game theory will find a way to impact the DisCos’ design, while its manifesto takes a critical standpoint from game theory.

In this context, two examples, one of a project and one of an idea, come to mind, intersecting with the DisCo. The project is Kleros and the idea is Futarchy.

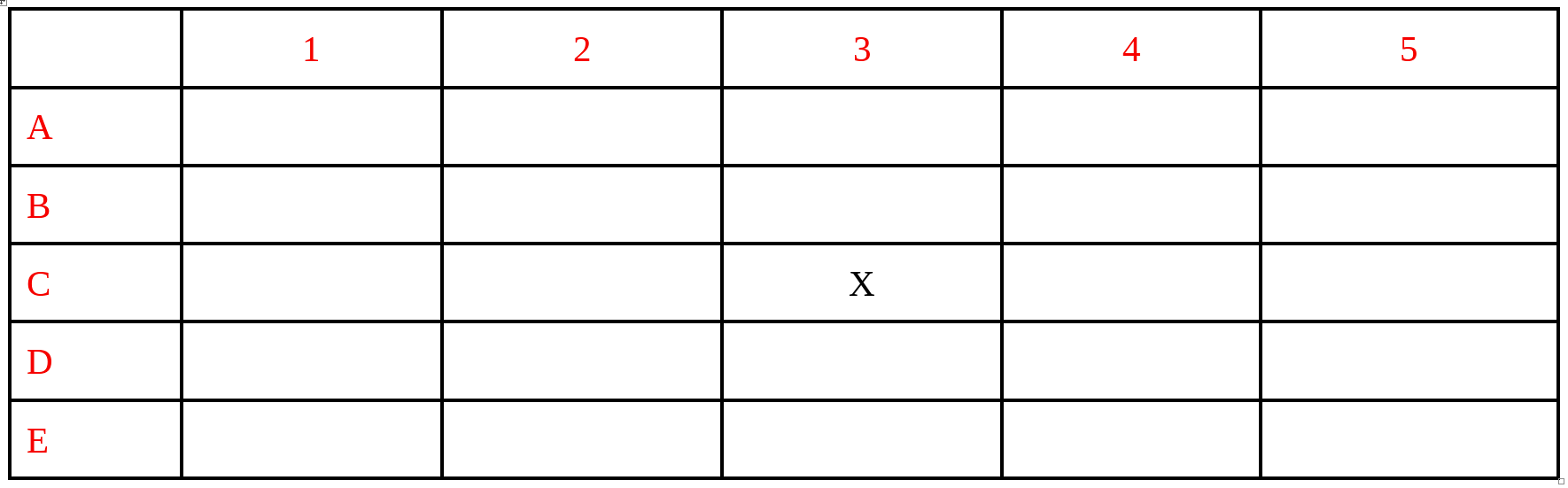

Kleros works as a mechanism for resolving disputes, incentivising those aligned with the majority focal point when considering disputing issues. Since this happens individually and in a decentralised manner, coordination becomes impossible, while each juror must try to align with the focal point if they want to be rewarded. It is important to note that the search for the focal point is not absolute but within the boundaries of the disputed contracts. This protocol is based, for example, on game theory in an application of the "Schelling Point", which states that people tend to choose box C3 in the below table when asked individually to choose the box they think will be most chosen by the majority.

Schelling point

I initially thought that this mechanism could be applicable to harassment issues. If work contracts were written and recorded on the blockchain, we might be able to delay the due payments until the work is completed and give everyone involved an opportunity to settle any disputes according to the agreed-upon protocol. If someone violates the code of conduct, they could be penalised and lose all or part of their payments, in addition to reputational slashing that could lead to a specified penalty period where a cancel verdict is executed.

However, I became unsettled by the idea, fearing that the psychological punishments would extend to a Black Mirror kind nightmare. It also seems like an extension of Carceral Feminism, believing more than necessary in punishment and ignoring crimes against women that occur at the same rate in countries with gender equality legislation like scandinavia. Despite that, punishments based on game theory appear to be a flexible tool that can be adapted in the form of transition between imprisonment and abolition.

As for Futarchy, it converges with DisCos in the concept of value sovereignty. It introduces the idea of financing in exchange for contributions to social welfare, allowing governments/smart contracts the opportunity for implementation and retroactive rewards based on people's satisfaction with their lives, while leaving the task of electing to prediction markets.

By prioritising social well-being over profit and growth, DisCos acknowledge and reward unpaid labour, cooperative relationships, and charitable endeavours.

Does this open the door for feminist projects that adopt well-being as their criterion? Perhaps. It may also encourage the emergence of systems based on experimentation. Could this be the only oracle in our era, where we can read the tea leaves?

Perhaps the DisCos will choose not to use these tools. It might opt for a model of playing that is deeply immersed in the playness of nature, as described in David Graber's What’s the Point If We Can’t Have Fun, not relying on "consciousness" and abandoning the left-wing dream of conscious masses. It may rely instead on the phenomenon of emergence as a political act that can be utilised, clustering around simple rules that give rise to intelligent intuitive systems, like an ant colony.

In this context, data-based governance could unleash many possibilities and the importance of data monopolised by major tech companies comes to mind. Projects of Augmented Democracy might guide governance and counter the manipulation of voter data. However, more important than its role in preserving integrity is its role as a tool capable of empowering these intuitive democracies without reducing people's voices to a simple "yes" or "no" vote.

This also contributes to liberation from the centralised identities. It allows for contradiction, negativity, and randomness to coexist alongside consistency and logic, connecting with the legacy of cyberfeminism when it released the "100 antitheses" that denied itself a hundred theories instead of issuing a defining one.

By simulating cyberfeminism, and through the phenomenon of emergence, perhaps I don't know and don't want to know what I want, but I know that patriarchy and matriarchy have been obsolete to me, because as George said to Martha in their film Who Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: “Our Son is Dead."

- 203 views

Add new comment