Image source: screenshot of the documentary Redes Comunitárias - Acesso à informação como Direito Fundamental by Instituto Bem Estar Brasil.

GenderIT and Locnet invited women who work in CNs to share their experiences in the times of COVID-19 and their reflections on what these times have revealed around centering meaningful communication in their physical and digital communities.

“If you can see, look. If you can look, observe." – José Saramago.

One of the senses dealt with in this phrase by Saramago is vision. However, it is not only about the physical act, but also how much is up to our eyes beyond seeing, observe. What do we watch? The implied meaning of Saramago's expression would be to observe more widely our experiences as a society, going beyond the physical senses and reaching social senses.

At the time when it was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) that the new coronavirus had spread across the globe (becoming a pandemic), we were faced with a series of rules of new social behaviour, which in general prevents crowding among people. The term “social distancing” started to be repeated by the mass media and was inserted in our daily lives as a mechanism to protect people against the spread of the virus.

Is it true that we can only see the island when we leave the island? Staying away from people was an exercise in noticing interpersonal relationships as well as institutions, organisations and social movements. To that end, the analysis of this article will focus on the possible relationships between popular education and community networks. This discussion was triggered by participation in the implementation of community networks over nine years (2011-2020).

I try to describe situations that permeate the construction of a community network that I coordinate in the Casa dos Meninos Association in Brazil, also linked to class, race and gender discussions. In the journey to implement the network and as a professional in basic education, I felt a synergy between these two teaching spaces.

The first part of this article is dedicated to analysing the contribution that the production of community networks may have for basic education, especially in this pandemic period where the discussion of information technology has been amplified in educational institutions. The second part tries to bring popular education closer to the methodology of building community networks, found in the works of Brazilian thinker Paulo Freire and the Black woman writer and Kentuckian, bell hooks.

Finally, I describe how the construction of community networks advances on technological appropriation, implementation of autonomous infrastructure and technical training dedicated to digitally excluded communities. I note also the need to analyse the roots that conditions these contrasts – for example, why there is no quality connectivity and technological knowledge for certain groups of society?

The construction of community networks and their contribution to public education in times of pandemic

At a time of pandemic and social detachment, the agenda of new technologies entered school life intensely. The adaptation of school education began to introduce the new Information and Communication Technologies as a way to continue the school year, using educational platforms and resources at a distance.

As a basic education teacher, I came across some questions. For example, how would students access classes? In Brazil, there are about 47 million Brazilians who do not have access to the internet and when they do, it is precarious.

The way in which technologies were included in educational paths during the pandemic period fuelled the expansion of companies such as Google, Facebook and Microsoft within educational institutions. According to the survey of the Vigiada Education Initiative in 2018: "65% of public education institutions in Brazil – universities, federal institutes, state education departments and municipal education departments in cities with more than 500 thousand inhabitants – are exposed to the so-called "surveillance capitalism", a term used to designate business models based on extensive extraction of personal data via artificial intelligence to obtain predictions about users' behavior and thereby offer products and services".Educação Vigiada, organised by Educação Aberta (in a partnership between the UNESCO Chair in EaD Education (UnB - Universidade de Brasília) and the EducaDigital Institute), and by the Laboratório Amazônico de Estudos Sociotécnicos and the Centro de Competências em Software Livre – both from the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). [https://educacaovigiada.org.br/#sobre](https://educacaovigiada.org.br/#sobre)

The way in which technologies were included in educational paths during the pandemic period fuelled the expansion of companies such as Google, Facebook and Microsoft within educational institutions.

The collection of personal data from students and education professionals is observed in the lack of transparency of companies that take advantage of this moment, positioning themselves as “donors” of educational systems and the state, which is absent in mediating this relationship.

During my participation in the online meetings of the São Paulo State Department of Education, I discovererd another question: how would these platforms be inserted into the daily lives of management, teachers and students? I witnessed little knowledge about the functioning and handling of digital tools (hardware and software), in addition to limited interaction of students in classes, who indicated lack of access to the internet, computers and adequate spaces to study. The pandemic has exposed social contrasts that already existed in Brazilian society,Soprana. P. 70 million Brazilians have poor internet access in the coronavirus pandemic. Folha de São Paulo. São Paulo, 16, Maio e 2020. Mercado. available in: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2020/05/cerca-de-70-milhoes-no-br…. accessed on 19-11-2019. and as research on access to information technology has gained strength in the last period, it has revealed that inequality of access is impacted by income, gender and race.

A survey launched by the Comite Gestor da Internet in BrazilTIC Domicilios. Research on the use of Information and Communication Technologies in Brazilian households. São Paulo, v. 15, 2019. available in https://cetic.br/media/analises/tic_domicilios_2019_coletiva_imprensa.p…. accessed on 18- 11- 2020. in 2019 revealed that 40% of people are disconnected, with 45% of families earning up to a minimum wage having no internet. Where 58% of all Brazilians access the internet exclusively through their cell phones, this percentage reaches 85% among the poorest population. The data also show that race is a determining factor for internet access and devices suitable for study and work. The exclusive use of smartphones to access the internet is prevalent in the Black population (65%), compared to 51% of the white population.

According to data from the report “The Mobile Gap 2018”,Rowntree, O. et al. GSMA Connected Woman – The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2018. GSM Association. Londres, 1st ed, pg. 14-22, March 2018. women are 15% less likely to be smartphone users in Brazil, compared to the global average, where women are 10% less likely to use a smartphone. Among the reasons, according to the survey, are the high price of products and services, the inequality of wages between men and women with the same occupation, and the limited number of opportunities for income generation, when compared to the male gender.

If the main source of internet access for the Brazilian population is via cell phones, being deprived of these tools means that low-income people are prevented from accessing services available through smartphone applications during the pandemic, such as, for example, the income supplement provided by the government or online classes. That is why it is so fundamental to create a mechanism for technological appropriation and production of knowledge in this area, as provided today by groups working in community networks.

Popular and technical education in community networks

Learning how to install a network and sharing that knowledge in the community where I live was fraught with conflict. As a Black woman living on the periphery, barriers of class, race and gender emerged as I engaged more deeply in this debate. These conflicts called into question my permanence in these technology discussion groups.

With the contribution of popular education literature, among it that of Freire and hooks, a new attempt to remain in these groups appeared, making it possible to discuss these social contrasts within the collectives that work with the objective of technological appropriation.

Learning how to install a network and sharing that knowledge in the community where I live was fraught with conflict. As a Black woman living on the periphery, barriers of class, race and gender emerged as I engaged more deeply in this debate.

Initially, the dialogue with technology activists was around the appropriation of this technical knowledge and the implementation of the network. Proximity to technicians increased through coexistence in workshops and events in the area. Technology-educated people generally had distinct social characteristics compared to the periphery, usually consisting of white, heterosexual and middle-class men. This distance has always been central to the discussions, one of which was how to take this knowledge to the periphery given all these barriers.

Workshops given by activists of free technology and digital culture were a methodological challenge. How can you get people to learn this information? We would often hear that “we would move forward if we had the discipline to study the subject”. That was a fact, but the questions remained – what would need to be learned? What order of subjects should be studied?

According to Bell Hooks: "Let’s face it: most of us were taught in classrooms where styles of teachings reflected the notion of a single norm of thought and experience, which we were encouraged to believe was universal".hooks, b. Teaching to Transgress - Education as a practice of freedom. Routledge.

The supposedly "universal" experience of learning technologies that defines the workshops and courses in which I participated, even if taught by friendly and highly committed people. The point in question was not the unwillingness of these people, but rather understanding different mechanisms and methodologies that would bring people closer to the content. One of the suggested methodologies is Freire's popular education, as described by Antonio Fernando Govêa da Silva: "The proposal seeks to break the dissociation between scientific knowledge and citizenship, observed in the dominant socio-cultural tradition, of the colonizer, considering knowledge, both the local reality – a reflection of a socio-historical context, concretely constructed by real social subjects – and the production process of academic culture, proposed from the dialogue between knowledge, popular and scientific, in which the apprehension of knowledge is built collectively, from the analysis of the contradictions experienced in the local reality".Silva, A. F. G. A busca do tema gerador na práxis da educação popular - Metodologia e Sistematização de Experiências Coletivas Populares. Gráfica Popular, Curtiba, 2 ed., pg. 13-16. 2007.

Teaching in community networks using methodologies that experiment with different forms of knowledge production and learning can lead to disruption of dominant teaching practices. When I met the feminist collective Marialab, who works with technology and feminist courses for cisgender and transgender women, something started to change.

The debate provided by Marialab presented a series of improvements in the methodology of network workshops, including those that contained exclusively men. I noticed leaders of groups that implemented networks being approached about how their behavior excluded women from the learning process. As bell hooks wrote, “To educate as the practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn.”

As bell hooks wrote, “To educate as the practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn.”

These episodes opened space to think about other issues that permeate the environment of community networks, including at Casa dos Meninos. The network's workshops have always been aimed at teenagers aged 13 to 18 years old. When we had exclusive workshops for girls, it was difficult to get an significant number. It was very rare to finish workshops with attendance by girls from beginning to end, unlike the more steady attendance by boys.

We found that, not by chance, participation in domestic work was one of the factors preventing girls from having access to technological education provided by the association. This corresponds with the statistical survey carried out by the National Forum for the Prevention and Eradication of Child Labor (FNPETI), with data from the National Household Sample Survey (Pnad) 2014. In this research it was demonstrated that domestic child labour is in general reserved for girls – 94.2% of child labour is performed by girls. Of these, 73.4% are Black and 83% perform household chores at home in addition to working at the home of others.

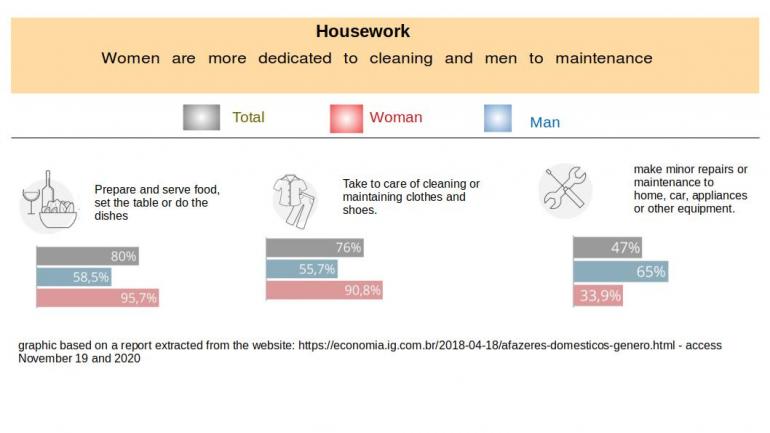

In the diagram below, we can see the current distribution of tasks within Brazilian homes released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics in 2017.

This picture reveals situations that were repeated several times in the workshops. Eventually I went to these girls' houses to look for them, in order to find out why they were absent. Most of them were busy taking care of younger children, cleaning the house and cooking.

Building community networks means thinking about those considerations that affect the present and future of women. The Freirian methodology of popular education has a technique of analysing the local reality before thinking about the production of knowledge. As explained by Antonio Fernando Govêa da Silva:

"The preliminary survey of the local reality, participatory action research, seeks to start from data collected in the community (statistical, socio-cultural, economic, political and linguistic), which are organised so that the situations considered significant are related, in the sense of:

- Evidence of different views and perceptions of the different segments of the community.

- Interrelate data and information that allows configuring the studied reality.

- Collectively analyse and contextualize local phenomena in society.

- Explicit contradictions that, in principle, may be hidden from the majority of the community.

- Enable the analysis from the contributions of systematised knowledge, generating content that proposes to overcome the previous vision, the construction of critical conceptions about the real."

As a method that offers a better diagnosis of the community, this set of values serves as a major contribution to the work of community networks. One concrete step that could be taken, for example, would be a preliminary study of the local reality that indicates whether child domestic work prevents girls from obtaining knowledge.

The Freirian methodology of popular education has a technique of analysing the local reality before thinking about the production of knowledge.

Conclusion

Social inequalities are often present in places where there are projects for community networks, which are needed because there is a lack of public policy that addresses the basic needs of people, such as internet access and training in technology, among others. The free/libre technology groups already condition their work to reduce the existing inequalities by being transforming agents. However, the thread that connects these injustices is linked to economic and social issues. Critical appropriation of technology can unfold in community actions that guarantee access to fundamental rights, such as basic sanitation, education and quality health.

When dealing with the relevance of community knowledge in territories where we develop network projects, we find several issues common to the process described by Paulo Freire in “Pedagogy of Autonomy”.Freire, P. Pedagogia da Autonomia - Saberes necessárias à prática educativa. Paz e Terra. São Paulo, 1ed.,pg. 55-111, 1996. If it is the communities in these territories that experience structural inequalities, it is necessary to highlight these issues in order to move towards social justice.

Critical appropriation of technology can unfold in community actions that guarantee access to fundamental rights, such as basic sanitation, education and quality health.

Hooks analyses why we reproduce hegemonic practices in the teaching and learning processes: "The unwillingness to approach teaching from a standpoint that includes awareness of race, sex, and class is often rooted in the fear that classrooms will be uncontrollable, that emotions and passions will not be contained. To some extent, we all know that whenever we address in the classroom subjects that students are passionate about there is always a possibility of confrontation, forceful expression of ideas, or even conflict".[^2]

As uncomfortable as these issues may be, discussing them allows us to alter pre-existing privileges and to identify structures that shape an unequal society. Although these themes may seem fluid in those spaces considered more progressive, often they are not.

I was recently invited to build a community network in a quilomboQuilombos emerged as refuges for black people who escaped repression during the entire period of slavery in Brazil, between the 16th and 19th centuries. The inhabitants of these communities are called quilombolas. After the abolition, most of them preferred to continue in the villages they formed. With the 1988 Constitution, they gained the right to own and use the land they were on. Today Brazil has more than fifteen thousand quilombola communities. where participation was for women only. In addition to this being a novelty, it sparked a discussion during the project about race and community networks. One of the project's participants, a white woman, proposed that the debate should start with the concept of whiteness. It was a moment of relief and happiness to witness the group's intention to address the responsibilities of whiteness in maintaining racism. This episode shows how we can reconstruct ourselves within these environments from the awareness that we are beings under construction. As Freire wrote: "Here we come to the point that perhaps we should have left. That of the unfinishedness of a human being. In fact, the unfinishedness being or its inconclusive is characteristic of the vital experience. Where there is life, there is unfinishedness".

The willingness to participate in the construction of an egalitarian society presupposes putting us in a state of constant review, making it possible to interfere, decide, compare and reject. I see popular education and community networks as places that can enhance social justice processes. Because of the strengths of its proposals, but also because it is an inconclusive process and is in dispute, there is still the possibility of intervention and the practice of freedom.

I see popular education and community networks as places that can enhance social justice processes.

- 5012 views

Add new comment