Comic by Sylvia Karpagam

Rasimma loved the poor and oppressed. She loved them so, so, so, so much, so much. She loved them so much that she was ready to do anything for them – as long as it didn’t affect her friendships, her salary, her cosy spaces etc. She lived in an agrahara, which was swarming with friends and family from oppressor communities. She occasionally expressed her sadness and grief at the rampant oppressive practices in her “ghetto”. ‘I feel so bad you know’ she would say in moments of deep introspection. ”My child only speaks brahmanese. I do try to teach her the local dialect, but whatever… ’ Rasimma had tried, somewhat valiantly, to leave the “ghetto” and live in a less oppressive neighbourhood, but couldn’t because her husband loved the place, and she loved her husband.

My child only speaks brahmanese. I do try to teach her the local dialect, but whatever…

She also had a series of unfortunate encounters with her ‘maids’. In all instances, she had been wonderful to them and in all those same instances they had stabbed her in the back (ouch!!). The ‘maid’ to whom she had given a loan had bad-mouthed her to a neighbour. The ‘maid’ who she allowed to eat in her house, and even from her own plate at times, had failed to clean the corners of rooms and needed constant reprimanding. The ‘maid’, who seemingly loved her child and who her child loved right back, left one fine day for greener pastures. “I treat them like family,” said Rasimma “I don’t treat them like servants, but none of them has had any gratitude” All these things had hurt Rasimma deeply and she shed quiet tears when she had a sympathetic listener. She felt that she had never been truly appreciated and that her deep sense of commitment to the oppressed had been underestimated.

She had nuanced positions on every subject while never taking a proper position on any. She believed in strategy. Her most strategic strategy was to hunt with the wolves and cry with the lambs (so to speak). While her heart bled for the oppressed, she made sure that no oppressor felt unwelcome in her heart and home. Being the sensitive soul that she was, she hesitated to invite the poor to her house, in case they felt too overwhelmed by its opulence. She knew she had no such moral dilemmas with the rich oppressors. Visitors to her house, therefore comprised only those from rich oppressor communities.

Her organisation’s motto was inclusion and diversity. All those from the oppressor communities were in senior, well paid, permanent positions. All those who were from the oppressed communities worked as housekeeping staff and security on contract with an agency. Any labour law violations faced by those from the oppressed communities were attributed to the agency. Her organisation claimed to have no control over the contract-agency, so the violations continued unchecked. Housekeeping staff lost daily wages for any leave they took and they had never heard of provident fund, health insurance or labour rights. Rasimma’s colleagues, on the other hand, had all this and more and were in fact fighting with their boss for period-leave. The period-leave didn’t extend to the women who were housekeeping staff because they, of course, came through an agency!

All those from the oppressor communities were in senior, well paid, permanent positions. All those who were from the oppressed communities worked as housekeeping staff and security on contract with an agency.

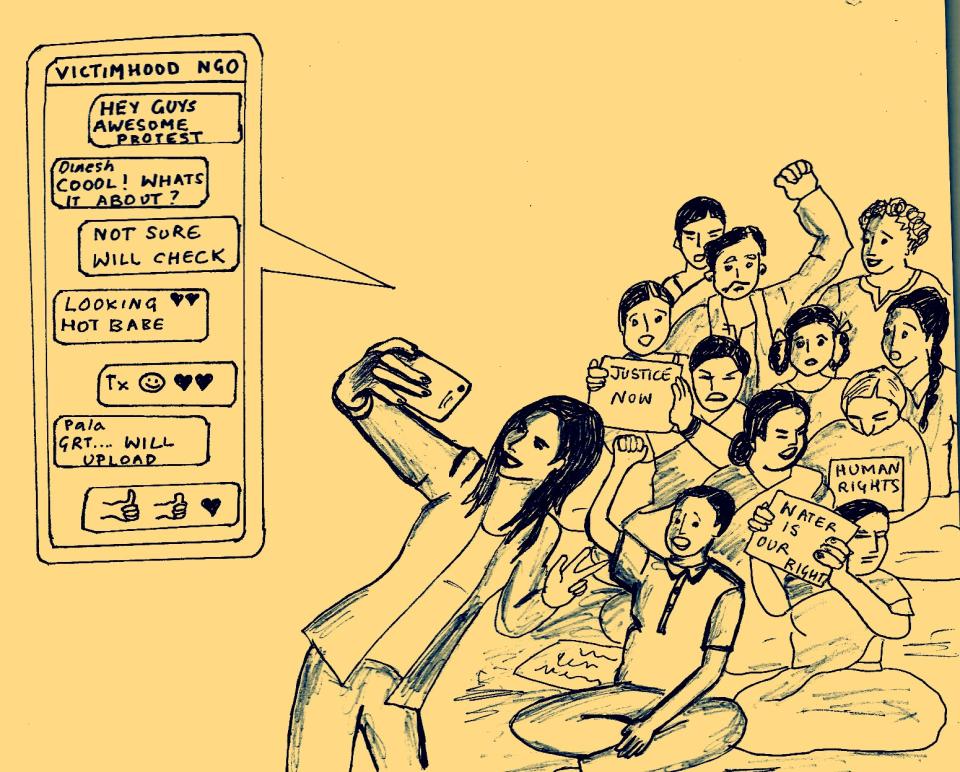

Rasimma’s organisation claimed to work on victimhood. They were present at different protests in the country, mostly organised by someone else and made sure to take several selfies at the protest. These would be shared on their work WhatsApp group appropriately titled “At a garment workers protest. More power to these awesome women’ or ‘ Feel part of something huge. Child rights and I” or ‘dalit women are sexually abused every day. Feel proud to support them to empower themselves’. Upon sharing these on their WhatsApp groups, they would be inundated with compliments ‘Hey, babes great work. Keep up the good work!, ‘Ohh awesome that you work with these poor people. God bless and keep up the spirit’ etc. One lady, who had posted a selfie of herself with ‘a tribal woman’ was asked on the WhatsApp group how she dealt with the emotional trauma that the tribal women faced. “Oh I just drink myself to sleep’ she responded. Selfies kept the organisation going. It seemed like, as long as a selfie was posted, then the person posting the selfie had done all the work. This justified the lakhs they received in salaries.

Upon sharing these on their whatsapp groups, they would be inundated with compliments.

Comic by Sylvia Karpagam

All the employees in the organisation claimed to have their own personal victimhood. While her boss claimed that his dark skin offered him victimhood, another guy claimed language barrier. A third claimed geographical victimhood, while yet another claimed to be discriminated because she wasn’t doing any work. The fourth felt that her victimhood lay in her youth and that her ignorance and arrogance were being used against her by people who claimed to have more experience. This last, particularly tore at Rasimma’s heartstrings because it reminded her of her own youth. In Rasimma’s search for her own victimhood, she wondered if her rural upbringing gave her the right shade of victimhood. She occasionally brought this up, in a timely manner, to demonstrate her humble roots and branches. IT WORKED !!!

Soon Rasimma’s humility was the talk of the town. She was invited to different talk shows and events. She humbly accepted all the accolades which she knew she richly deserved. The more rich and famous she became, the more humble she became.

Her organisation, in the meantime, had decided to work on sexual violence. Their media team went into over-drive. They collected ‘poor and oppressed women’ and asked them to disclose all the sexual violence that they had undergone. This was recorded on a hi-tech camera and put up on all the organisation’s social media. It was even projected to large corporates to mobilise donations – the catchphrase being ‘she is a woman too. Help us to help her.’ The videos brought tears to the eyes of the corporate staff and tugged enough at their heartstrings to make them loosen their purses and donate several thousands of rupees. This would help the organisation take more selfies and mobilise more funds. The women who had been sexually abused got nothing in return – not even a travel fare. They would have, of course, felt part of some larger movement for some unfathomable good.

They would have, of course, felt part of some larger movement for some unfathomable good.

When the social media had erupted over the fate of the poor sexually abused women, nominations for awards to the organisation and its most visible employees flew around. It was no surprise to anyone that Rasimma was nominated for ‘a Life-Time Service to the Oppressed Award (LTSOA)’. In her speech, she said “I love the oppressed. I will give my life for them. While I understand their pain and suffering, my sincere advice is to strategize. Act like you love the oppressor. Don’t challenge them. Don’t question them. Be like me. I came from such humble roots and have now reached such extravagant heights.’ She then gave a humble smile and walked off the stage.

Amidst the roaring applause, her oppressor friends swarmed around her clicking selfies and showering love on her. Her colleagues put up the selfies on their Whatsapp group and she received even more praise and love. She really felt so humbled by it all. Her organisation continued to grow and the employees promising to remain faithful to the organisation until their pension plans were confirmed. Their social media had reached a dizzyingly record number of followers. Sexual violence continued unchecked – but, hey, one can’t have everything, can you?

One can’t have everything, can you?

- 4647 views

Add new comment