Image description: Grafitti saying mmm i heart porn. Source: Wrote from Wikimedia Commons

In this article, we discuss the role of women as consumers of pornography, and we will also address female participation in its production. We focus on explicit sexual content consumed online by women, be it professionally produced or not--although. The majority of the contents we have in mind for the purposes of this discussion is marketed by the porn industry. The internet has made porn more readily available, including to women, and new digital technologies have further blurred the producer-consumer relationship. A female porn audience is not something novel, but one that has been systematically erased by a focus on heterosexual men as both the subject and the audience of pornographic narratives. Digital media facilitated women’s access to porn, while also enabling the selection of content particular to their tastes. This increased the visibility that women liked pornography, and the porn industry rapidly realized it was a niche worth exploring.

Digital media facilitated women’s access to porn, while also enabling the selection of content particular to their tastes. This increased the visibility that women liked pornography, and the porn industry rapidly realized it was a niche worth exploring.

Following the premise that porn is a form of knowledge regarding sex, we propose some questions: What is the role of the internet in the relationship between women and porn? What the pornography consumed online by women informs about female sexuality and desires, and the way they are perceived and marketed? What women who consume porn specifically enjoy about these contents? How the notion of a female gaze, a female audience, of a female taste in pornography has been interpreted, appropriated, and catered to? How it relates to the way porn is produced and consumed? There are no definitive answers to these questions, but we propose a critical feminist perspective to look at these issues and to consider the potentials of feminist porn to help address them.

As authors of this article, we examine these phenomena coming from two perspectives: our social sciences training, and as consumers of this content ourselves. We thus argue for an ethnographic perspective, looking at what is familiar and trying to put it in the unfamiliar terms of analysis. Our approach to this issue also comes from a profound sense of anguish about the current state of porn as a product we consume (as the authors of this piece, as individuals, as a society). For us, this is a discussion about the ethics of porn consumerism and production, framed in terms of a change in the sensibilities about how pornographic content is (or should be) consumed. We ask, from a feminist point of view, how can we consume porn ethically?

We believe the rise and fall of James Deen as a porn star serves as an illustration of this debate. Lauded briefly as an expression of what women wanted to see in porn, he now stands accused of sexual assault by the women he performed with and, in some cases, dated. Deen’s rise helped show that women liked porn, and what kind of porn they could like. His performance and type of scenes--rough but romantic--became popular among women, his success going even beyond the porn industry (Zilli, 2012 explored this success at its beginning). If James Deen rise to stardom helped visibilising that women were porn consumers, his fall left a bad taste in the audience’s mouths. In late 2015, porn screenwriter and performer Stoya, a frequent scene partner for Deen, and former girlfriend tweeted that he had repeatedly ignored her safeword, and raped her. Suddenly, Deen’s audience had to struggle with the idea that they had watched him abuse a woman right in front of their eyes.

Pornography today is a multimillionaire global industry, with revenues in billions of dollars annually. With the expansion of web 2.0, pornography achieved a unique platform. Porn content became merchandise readily available and accessed, in many cases free, something that affects performers directly. Porn has traditionally been centred on the objectification of women and is permeated by symbolic subjugation. At the same time, porn is a space where fantasies and sexuality can be explored. In the annual audience and traffic surveys published by sites like PornHub, for example, 28% of the audience is female (even though PornHub data is collected without a username or password being required, which compromises metrics about the user’s gender). PornHub created in 2018 the category “porn for women”, and algorithms now suggest hashtags like “popular with women”, “passionate sex”, “romantic”, and “women-friendly”.

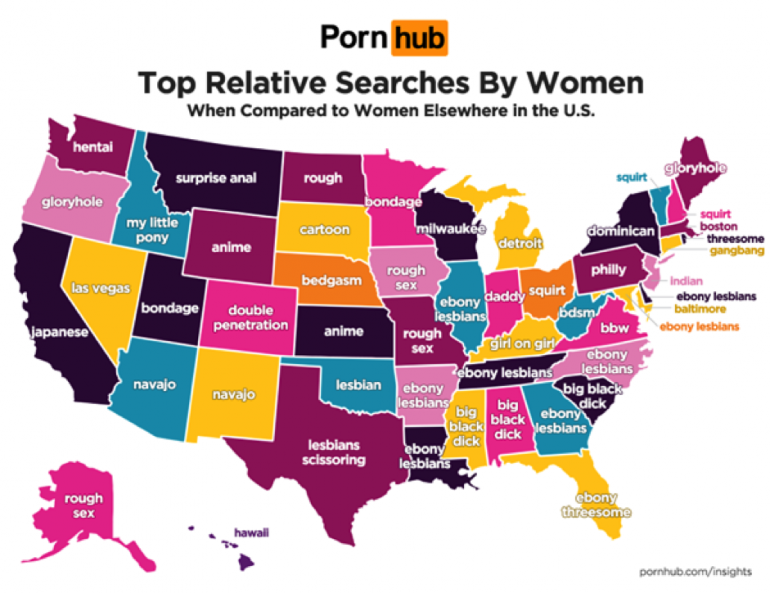

However, as can be seen in the US-centered example in the image below, women's interest in pornography cannot be precisely categorized. Indeed, sexual fantasies and the exercise of sexuality are social constructs, and any generalisation by gender or any other social marker is just that -- a generalisation. Traditionally, the porn industry has been majorly controlled by men, and target at them. That is, the same perspective that produces content to cater to cis heterosexual men creates misconceptions and generalizations about what kind of porn (and sex) women like, and what kind of women consume such content.

Image description: Consumption patterns of pornography mapped on U.S.A. Source: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/women-of-the-world

In the last years, sites like PornForHer, Bellesa, and FrolicMe started to produce or disseminate content targeted at women. This so-called "women-friendly" pornography marketed by mainstream production is still associated with white satin sheets, rose petals, romantic music, and a couple in love. These productions not only still focus on heterosexuality as a norm, and in female homosexuality as its mere accessory, but also disregard that women’s pornography can be vulgar, intense, bold. Such non-threatening, non-intimidating content is a striking contrast to the rough sex that has become quite normalised in the mainstream pornography industry. Thus, women are relegated to a niche that understands their interest as exclusively linked to an ideal of intimacy, and those uninterested in these new productions end up ignored. It also erases the many possibilities of female desire, and that porn for women can have multiple forms—without being about women’s abuse.

These productions not only still focus on heterosexuality as a norm, and in female homosexuality as its mere accessory, but also disregard that women’s pornography can be vulgar, intense, bold.

Does this mean mainstream pornography cannot cater to the possibilities of female sexuality and desire? There is certainly a gap, and it is being occupied by several producers focusing on more realistic and less stereotypical sex, performed by and for women. Sites such as the XConfessions project, Erika Lust's Lust Cinema, JoyBear or Lucie Blush's work are not designed exclusively for women but propose precisely to take the focus away from the male gaze, where women are not in the scene solely and exclusively to satisfy the male pleasure. They present concerns about the diversity of bodies in the media and contemplate other sexual interactions beyond the heteronormative. The site Sssh, for instance, is presented as “the evolution of indie adult cinema. It's feminist porn for women and couples. It's porn, re-imagined”. Even a cursory look at the various websites offering this kind of pornography reveals similar discourses all across: if large-scale pornography does not represent me, does not satisfy me, and bothers me, I create my own pornography. All these sites indicate that they care about the ethics of their productions, such as: Create a safe sex environment for filming with every performer providing up to date STD checks (and performers choose whether they wish to use a condom); discuss and agree every part of the shoot beforehand with all performers, and never ask a performer to do something they have not agreed to or expect; pay every director or studio featured on the site commission from the sale of their films (https://xconfessions.com/values).

Erika Lust Films runs three online streaming platforms (Lust Cinema, Erotic Films and XConfessions); one store for downloads, toys and cosmetics; ... project working to encourage sex education for young people: The Porn Conversation. Thank you for your support. Here’s to a future of ethical, adult cinema (https://erikalust.com/fun-facts-about-the-lust-headquarters).

The term "feminist porn" has been in use to identify such productions created by and often targeted at women. The social and political discourse surrounding this new wave of pornography is based on discussions about work and consumption ethics in the porn industry, especially regarding the exploitation of women; as well as the need for racial and gender diversity both in front of and behind the cameras. The development of this “feminist pornography” occurs in the wake of the third feminist wave, with polarising opinions regarding feminism, pornography and sex work (Gregori, 2013 offers a review of the feminist sex wars that took place during the 1980s, its consequences and updates). As Feona Attwood (2007) rightly proposes, this debate inside feminism led to a paradigm shift in which pornography can be studied from the point of view of the context in which it is created; and not only thought of exclusively in negative terms, of the evils or consequences it causes to those who consume or perform in it. Parallel to this shift in focus, Attwood points to the gradual influence of cultural studies on this new perspective and the development of new currents of the feminist movement that support pro-sex attitudes as well as changes in media representations of sex and sexuality.

The social and political discourse surrounding this new wave of feminist pornography is based on discussions about work and consumption ethics in the porn industry, especially regarding the exploitation of women; as well as the need for racial and gender diversity both in front of and behind the cameras.

Deeply insightful analyses have looked into these and similar questions: for instance, Datta (2015) discusses the actual harmful effects of pornography, which is substantial to a reflection about its ethical consumption. The author singles out consent as a major element for establishing potential harm in pornography. Datta speaks about porn in reference to feminism and freedom of speech, rejecting the notion of a ban on porn and encouraging content creation aligned with these interests:

If we applied the free speech argument to porn, we wouldn’t ban porn. We’d fight porn with more porn, make more porn for women, counter-porn, more porn that makes us the subjects of our sexual journeys, pleasures and destinations (Datta, 2015).

The author makes a clear distinction about which kind of sexually explicit content should be banned: that which is produced or disseminated without a participant’s consent, a violation usually labelled as "revenge porn"--because in most cases it involves the publication of intimate contents that were shared under an assumed relationship of confidence. Petrosillo (2016) insightfully categorized this as a form of humiliation porn, because what really is in play is shaming the victim--almost always a woman.

The issue of consent is also central in commercial pornography, and highlights the urgency of discussing work practices in the porn industry, and what our role as consumers is. Even feminist productions struggle with issues related to sexual consent practices in pornography. In 2018, Lust Films faced a lawsuit with allegations of sexual abuse, including incidents of limit violation on film sets. Thanks in part to extensive media coverage and the recent interests of the audiovisual industry itself, public debates about women and the consumption of pornography already exist--but still face stigma. Pornography made for and by women is not just a sign of market segmentation, especially if we consider that nothing is consumed in a cultural vacuum. We are embedded in a culture of consumerism, in the sense that consuming includes and influences many spheres of life, being cultural and symbolic activities instead of merely economic practices (Campbell, 2001).

We are embedded in a culture of consumerism, in the sense that consuming includes and influences many spheres of life, being cultural and symbolic activities instead of merely economic practices

In this sense, pornography privileging the female gaze is an example of consumers producing that which they want to see. Many practices of pornographic consumerism, especially outside mainstream markets, are similar to the experiences of fans and fandoms in consuming and producing their own content (Jenkins 1996, Laai 2016). Just as fans use digital tools to produce and share their own videos, movies, animations and illustrations, women at the head of the so-called feminist pornography are “hacking pornography”. They are meaningfully taking the reins of this chain of production and consumption that is not properly contemplated by the mainstream pornography market. Director Lucie Blush's blog is a good example of these ideas, where she clearly states her motivation to produce pornography:

“I’m Lucie Blush. I’m 31 and I live in Spain. I started this blog five years ago as I found myself single. I knew sex had to be more than just the mechanical stuff we see in porn. I’ve always had a strong imagination and I went on a search for hot, erotic, pornographic videos that satisfied me. I opened a very deep box and started writing about my own sexual journey here, sharing my thoughts and questions. Then, it was clear. I had to make my own movies. And I did. Here you can watch all of them: CommonSensual.com” (https://www.welovegoodsex.com/about-lucie-blush/).

These initiatives represent a shift, from consumers to producers of a content that can directly engage other consumers. In this context, we believe that a collective discussion about porn is necessary among women, whether in society, inside the academia, feminisms, within the porn industry, and especially in our own intimate spaces. Expressing and sharing common experiences with pornography and / or consumerism related to sexual desire would be an important step to advance debate about its ethics and an understanding of pornography as an instrument of female sexual agency.

Expressing and sharing common experiences with pornography and / or consumerism related to sexual desire would be an important step to advance a debate about its ethics and an understanding of pornography as an instrument of female sexual agency.

- ATTWOOD F. (2007) No Money Shot? Commerce, Pornography and New Sex Taste Cultures.Sexualities. Volume 10, issue 4. Pp. 441-456.

- CAMPBELL. C. (2018) The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism - New Extended Edition. Palgrave Macmillan.

- DATTA B. (2015) Porn. Panic. Ban. 2015. Available at: https://www.genderit.org/feminist-talk/porn-panic-ban.

- GREGORI M.F. (2013) Pleasure and Danger: notes on feminism, sex shops and S/M. CLAM. Sexuality, Culture and Politics - A South American Reader. Pp. 390-405.

- JENKINS H. (1996). Textual poachers: television fans & participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

- LAAI T. (2016) A identidade de fãs de quadrinhos: entre a “vida civil” e a “vida nerd”. Thesis (Doctorate in Anthropology), Fluminense Federal University, Philosophy and Human Sciences Institute, Anthropology Departament. Niterói.

- PETROSILLO I. R. (2016). Esse nu tem endereço: o caráter humilhante da nudez e da sexualidade feminina em duas escolas públicas. Dissertation (Master in Anthropology) – Fluminense Federal University, Philosophy and Human Sciences Institute, Anthropology Departament. Niterói.

- ZILLI B. (2012). A star is porn? Internet and a kind of porn women like. In: Association for Progressive Communications (Eds). Critically absent: Women’s rights in internet governance. Pp. 20-25.

- 7843 views

Add new comment