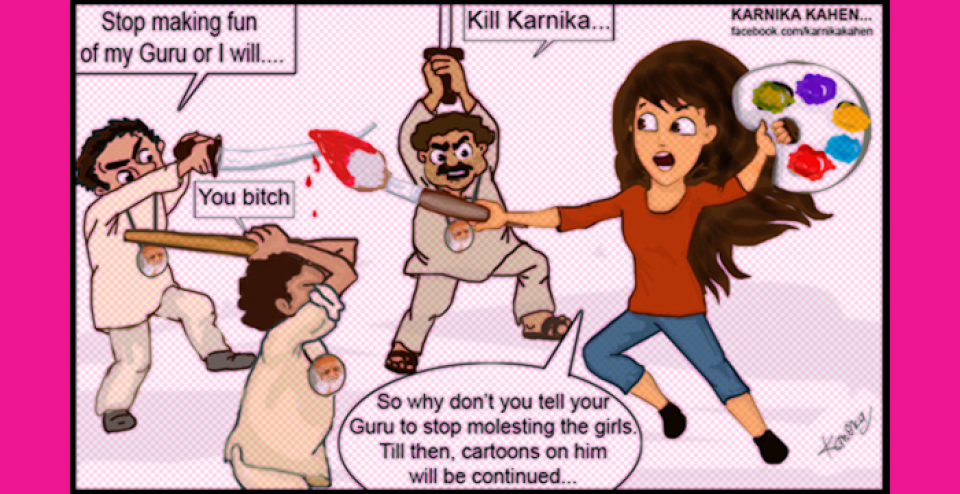

Image Source: Cartoon featuring character Karnika Kahen created by Kanika Mishra

In the current world, with so much of our lives online, it is important to remember that the negatives from the physical world also translate online. The patriarchal norms from the offline spaces also occur online. Violence against women and other gender and sexual minorities in an effort to silence them is a common occurrence. This violence can range from aggressive comments and trolling to rape and death threats, to doxxing and release of private information and/or photos which can cause physical harm to the person involved or those connected to them. As in the offline space, it is important to level the playing field with regards to ICTs and the internet as well. Take Back the Tech! (TBTT), initiated in 2006, is one campaign that aims to do exactly that. TBTT aims to reclaim technology as a main way to combat violence against women and other minorities.

This includes using cameras, phones, blogs, sites, podcasts, email, messengers, social media and more to ensure that the online harassment does not silence voices of those who do not adhere to the established norms of a conservative society. To truly Take Back the Tech, just combating online violence is not sufficient. It is also important to acknowledge contributions made by women in the historical development of technology as well as ensure that real access is achieved by women and girls. A collaborative campaign, TBTT has grown over the years with the participations of more and more organisations, individuals and initiatives. It has been organised in different countries and regions to respond to the local requirements of feminism, technology and violence against women. This makes TBTT a unique campaign, one that supports diversity not just for the sake of diversity but also to ensure that the campaign’s purpose is truly achieved.

To truly Take Back the Tech, just combating online violence is not sufficient. It is also important to acknowledge contributions made by women in the historical development of technology as well as ensure that real access is achieved by women and girls. A collaborative campaign, TBTT has grown over the years with the participations of more and more organisations, individuals and initiatives.

I speak to Japleen Pasricha of Feminism in India and Divya Rajagopal of WhyHate. Both are women who started initiatives in India in an attempt to get conversations going about feminism, violence against women and break the silence around the various issues surrounding women in India, including sexuality, reproductive health, abortion, alternative sexual and gender identities among other things.

Smita: Tell me a little about how Feminism in India (FII) and WhyHate began.

Japleen: Feminism in India began as a Facebook page in March 2013. Back then, it was just a random Facebook page with posts etc. and I didn’t really think about what I wanted to do with it. I was just switching into the gender and sexuality field and started working with Breakthrough in Delhi. When I was trying to learn about feminism, I started looking for memes, articles and other pop culture references, but I couldn’t get anything in the Indian or south Asian context. It was all on white feminism. This was the push for me to create original Indian feminist content. Since there was already a lot of offline work going on in India on gender, I didn’t want to repeat that. I preferred to fill the online gap which existed there. Our website was launched in August 2014. I already had some 1000 likes on the page, so we had support when the site was launched. Having a community helped. We had people who wanted to write on various issues for the site and so on.

Divya: WhyHate was started in 2014 and was actually part of my Masters program in Lund University in Sweden. In my thesis, I traced the origins of hate and focussed on gender based violence or hatred online, because this is not just someone thinking — “Oh she is a slut,” but they type it out and put it in the public domain. It seems like a manifestation of a medieval form of hatred in the modern times that targets women’s speech and expression in particular. Speaking and oratory of any form has been the domain of the man. Any attempts made my women to enter this domain was met with violence. This is what has been carried forward online as well.

An activist’s laptop at the EROTICS global meeting on sex, rights and the internet during our #imagineafeministinternet campaign. Photo courtesy of EroTICS India.

WhyHate was started to look at the experience of various female users of the internet across the world and in India who have come under attack for expressing their views. The idea was to get an empirical understanding of this hate. It was also to say that one cannot shut down speech in fear of violence, since the first reaction to trolling or threat online is to disable the account or stop using it. I want WhyHate to be something which is about chasing hate which comes on various social media platforms. I also want it to be a repository of information on internet, gender and hate. Right now, we just have a Facebook page. I’m currently working on this, collecting various case studies, reports and other things. Hopefully, we will be launching it sometime next year, perhaps by April-May.

Divya: We started to look at the experience of various female users of the internet across the world and in India who have come under attack for expressing their views. The idea was to get an empirical understanding of this hate.

Smita: Have you personally or your initiatives faced online harassment? If yes, what was it regarding and how bad did it get?

Divya: I have been targeted online personally, yes. It was Maha Shivaratri and I made a post saying something about how Shiva’s genitals are worshipped. In hindsight, it really wasn’t a smart move but I had done it. I had police complaints filed against me on the charges of “offending religious sentiments.” I was scared when I saw the comments on this, scared to live in my house. I stayed at my friend’s place for a few days. It was a terrifying experience for me. Apart from this, I had made these two videos for TBTT, interviewing two women, Kanika Mishra, a cartoonist based out of Bombay who got targeted after she posted a cartoon commenting on Asaram Bapu, a god-man accused of sexually abusing a minor girl, and Emma Holten. Emma’s intimate photos were put up online after her social media accounts were hacked. They were viewed by thousands and she received countless messages harassing her, and so she decided to get a set of nude photos of herself clicked consensually and put them up herself.

Japleen: We generally receive a handful of harassing messages on a daily basis. But recently, Ola Cabs came up with a new advertisement to promote Ola Micro and we pointed out that it was sexist. This led to a lot of MRAs on Twitter trolling us and asking us “to chill.” It actually exploded after one of the popular comedy handles @trendulkar commented on our tweet and encouraged others to tell us to chill, have a chill pill or whatever. This is an instance when we received a lot of harassing messages.

Another time was when we launched our new editorial policies. As you may know, we put up these new editorial policies saying that men will not write on women, cis persons will not write on transpersons, straight people on queers, upper caste persons on lower caste and so on. Now, these seemed like a really logical set of ideologies to us to avoid appropriation by the majority. But it took a whole new turn. When we received a lot of messages in support, we also received a lot of flak for this. Unlike the last time, this time it was the liberal and progressive ones who attacked us, people who we thought were allies. It was actually more upsetting than the other incident of online harassment. On a personal level, I have just stopped responding to them. It’s just something which happens if you work in the field.

Japleen: We put up these new editorial policies saying that men will not write on women, cis persons will not write on transpersons, straight people on queers, upper caste persons on lower caste and so on. Now, these seemed like a really logical set of ideologies to us to avoid appropriation by the majority. But it took a whole new turn. When we received a lot of messages in support, we also received a lot of flak for this.

Smita: That is really something. I’m sorry that you had to deal with that, but it’s the sad reality. Japleen, how did you respond in these two instances? Did you consider going offline?

Japleen: No, we won’t leave the internet. During the two instances of harassments which I spoke about, we adopted different tactics. In the first, we didn’t really engage with them as they were trolls and MRAs. In the second instance, we actually tried to engage with the people who criticised the policies, since they were people who had spoken to us and supported us previously. We tried to explain that we didn’t want to stop the straight or upper caste people from writing altogether, but we just didn’t want to support appropriation.

Smita: I completely agree with you on that. So what do you think are some of the things that have to be done to ensure that women and minorities and their rights are protected online?

Divya: In communications theory, there is something called the muted group theory which says that groups which have been muted in the society, LGBTQ, women, blacks etc, have a tendency to mute themselves in fear of sounding less intelligent etc. The Internet helped break through this, largely because the barriers to entry is so low. So it’s all the more important that we preserve the internet and the way it functions. I think this is a huge responsibility for the tech companies to make sure that their platforms are safe. If you see the rigour with which they work for tracking and/or banning terrorist groups, I think they can easily do the same with regards to gender based harassment. Why is the terrorist more serious than a sexual offender? Next step, the governments have to intervene. This is tricky since the question of censorship comes in here.

Smita: How much of a role would anonymity and privacy play in this, and how can this be ensured?

Japleen: We think anonymity is extremely important, and hence our discontent with Facebook’s Real Name Policy. Actually when we conduct social media trainings, we inform people on the privacy policies of Facebook, Twitter etc. And yes, anonymity is a double-edged sword but we still think it is of utmost importance. On an organisational level, we have a have guest writer account which we can use in case someone wants to write anonymously. We encourage people to use a pseudonym for the byline as it’s always more interesting to read something written by a person than to read something written by Anonymous. We also don’t compulsorily take social media handles etc. and don’t tag people if they don’t want it.

Divya: When I think privacy is very important, anonymity is a more dubious terrain according to me. If the trolls are using this for harassing me, I don’t think that their identities should be protected. Privacy on the other hand has to be protected.

A note during a workshop at the EROTICS global meeting on sex, rights and the internet during our #imagineafeministinternet campaign. Photo courtesy of EroTICS India.

Smita: But Divya, in a country like India, where anonymity is essential for LGBTQ persons, survivors of sexual assault and domestic abuse etc, wouldn’t lack of anonymity work counter to their safety?

Divya: I think for that, there has to be policy level changes. I think it is important to have national laws with regard to the internet as well. So those laws have to ensure that the vulnerable groups are protected. I don’t think my online abuser deserves to be online with the same protection.

Japleen: Whenever the topic of sexuality comes up, I feel like anonymity is paramount. Anonymity is required for women’s free sexual expression. It is required for LGBTQ persons to meet others from the community, for them to express their stories. Right to anonymity and privacy go together here. And given that we live in the time of “revenge porn” as it’s called, or image based sexual harassment, it’s all the more important. As women’s rights organisations, when we talk about sexuality, we talk more about violence and not enough about the consensual pleasurable aspects of sexuality. For that, right to privacy and anonymity is necessary.

Japleen:As women’s rights organisations, when we talk about sexuality, we talk more about violence and not enough about the consensual pleasurable aspects of sexuality. For that, right to privacy and anonymity is necessary.

Smita: So you mean that the right to anonymity also has to be more nuanced?

Divya: Yes. For example, I’m not okay with Facebook’s Real Name policy in the sense that they have the responsibility to not give my details to the government. To ensure that there is no gap in this, we the stakeholders will have to sit down and draft the laws. For example, if we had strong whistleblower laws then we won’t need anonymity. The ground level laws should be strengthened so much that anonymity will not be required. Free speech and expression laws have to be strengthened to protect activists in a democratic society. I don’t think the abusers should benefit from anonymity.

Smita: What can women and minorities online do to ensure that they are not silenced, especially considering we live in a country like India that does not have explicit privacy and anonymity laws. What do you think we can do, especially from a technology angle?

Divya: I think counter speech has to be strengthened. We also need to hold the intermediaries and the government more accountable for online violence against women and harassment. We cannot be doing all the work here.

Divya: We need to hold the intermediaries and the government more accountable for online violence against women and harassment. We cannot be doing all the work here.

Japleen: I think the first thing to do would be to occupy the space. We need to reclaim technology and the online space. We can do that by creating more content, speaking out more on social media and generally just being there. The second thing would be to support each other online. Allyship is important.

For example, just today there was this article on the girl whose google cloud was hacked and someone threatened to put up her private photos online and send them to her family and friends. She in turn put up a Facebook post outing the issue and asking for help in catching the harasser. In this case, since she is in another country, I may not be able to assist her directly, but I can help by sharing her post and her story. The word will spread. Moreover in cases like this, reading about one woman standing up to her abuser will help the others do the same, especially if she has support from the others. Sending a message of solidarity and support to others who are facing harassment and standing with them will go a long way.

Smita: Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts.

Japleen: I think the first thing to do would be to occupy the space. We need to reclaim technology and the online space. We can do that by creating more content, speaking out more on social media and generally just being there. The second thing would be to support each other online. Allyship is important.

- 10472 views

Add new comment